Taylor 101: Dispatches from the World’s First Taylor Swift Conference

It’s 8:30 a.m. on a Friday. The house lights glow warmly inside the Buskirk-Chumley Theater in downtown Bloomington, Ind. Pop music plays in the background as seats begin to fill. There’s a buzz in the historic theater, where silent films and early talkies once brought locals a taste of Hollywood glamour and grit.

Two girls in sequined tunics and sparkling pink headbands scamper in and claim seats near the stage. They shimmer like apparitions from the forgotten Hollywood days. Outside, a line is forming on the sidewalk. Three women, walking down Kirkwood, sidestep the crowd and pause to stare up at the iconic marquee:

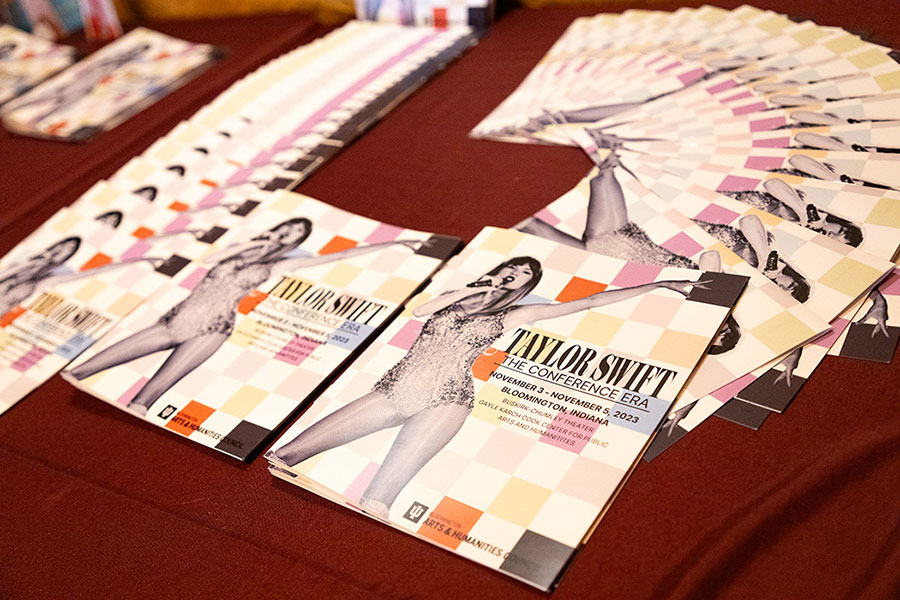

Taylor Swift: The Conference Era

Indiana University Arts & Humanities Council

Sold Out! Fri Nov 3 & Sat Nov 4

“What? Is she here?”

“No way.”

They consider the sign again.

“Wait…way?”

Sadly, the answer is no way. The IU Arts and Humanities Council—the conference organizers—made it clear from the outset that Swift would not be in attendance at the first-ever academic conference to focus exclusively on Swift’s music and influence. Yet, her absence did little to detract from the excitement gathering around the first day of this historic event, which brought together scholars of an array of disciplines from institutions in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

Big Reputation

Let’s say you’ve been hiding away in the woods (in a moss-covered cottage) since October 2022—around the time Swift announced her Eras Tour—a show that is more than three hours long and features 44 songs that represent each musical era of Swift’s discography. Secluded though your woodland hermitage might be, you probably could not escape from headlines such as these:

- Taylor Swift Concerts Are Generating Seismic Activity (Smithsonian Magazine)

- It’s Taylor Swift’s Economy, and We’re All Living in It (Wall Street Journal)

- More Than Half of U.S. Adults Say They’re Taylor Swift Fans, Survey Finds (Forbes)

- Person of the Year 2023: Taylor Swift (TIME)

- Taylor Swift celebrates boyfriend Travis Kelce’s NFL win (BBC)

- ‘Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour’ Breaks Disney+ Record as No. 1 Most-Streamed Music Film (Variety)

According to the internet, Taylor Swift is a good girl, a bad girl, the girl next door, a white girl, a femme fatale, an Americana girl, a practitioner of witchcraft, a literary genius, a musical prodigy, an overrated singer, a greedy capitalist, a compassionate philanthropist, and so much more. In the media melee, one can instantly find arguments to support any of these identities, and, oddly, all of them at once.

Scholars have been studying and writing about Swift for only about a decade, but increasingly as she reaches supernova status. As of 2024, she is the most-streamed female artist on Spotify and the most financially successful female musician in history.

Famously (or infamously, depending upon your stance), Swift also has detractors, including some who wrote to IU Arts and Humanities Council to object to the conference—an experience described by one of the conference organizers as “letters from established professors because they think you’ve sold out by having a Taylor Swift conference.”

While the blaze of opinion surrounding Swift could stoke social media platforms evermore, scholars across the world are engaged in serious interrogations of the artist’s work and social influence. IU’s conference is both a forum for new scholarship and a celebration for scholars who are building a body of knowledge together, many of them meeting each other for the first time. It’s also a celebration for fans who have come to share their experiences and delve more deeply into Swift’s artistry and influence.

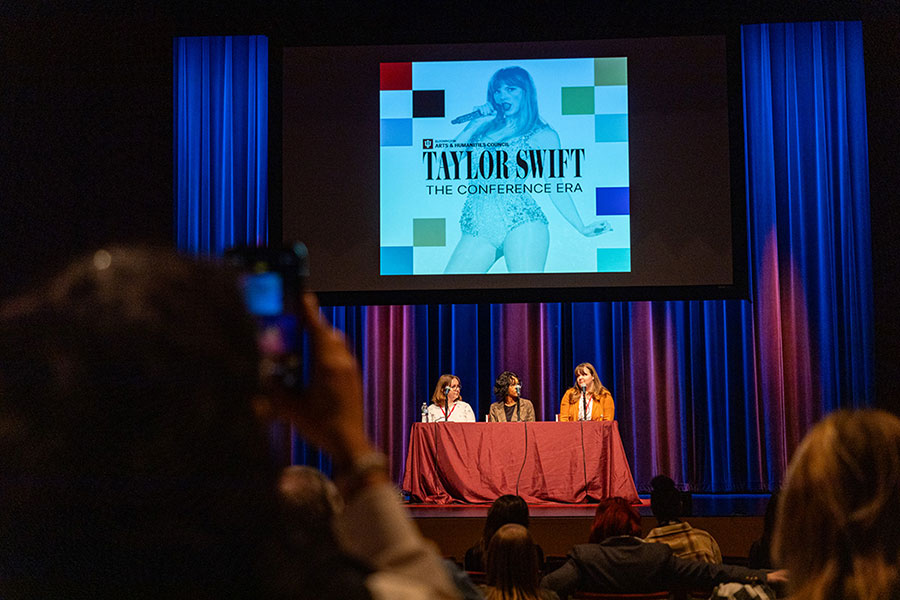

Over the course of the two-day conference, held in November 2023, nearly 30 scholars and experts examined Swift’s music and methods—investigating the roles of memory and nostalgia; musical genre and style; queer temporality and the politics of longing; Lacanian aspects of Swiftian imagery; feminism, escapism, TikTok and Myspace; and feline fandom.

Academia, Bejeweled

It’s abundantly clear that the number of sequins per capita in the theater is higher than average for an academic conference, an early indicator of the unconventional atmosphere that will prevail over the next two days. Yet, many academic traditions are firmly in place: the scholar-presenters; the faculty and students of the host institution; panel discussions; and the podium with the pesky laptop—which will, and sometimes will not, allow the presenters to show their slides.

Swifties of all ages are here, the youngest with their parents. Established fans mingle with the newly converted, beloved on social media of late for their earnest efforts to learn lyrics before the Eras Tour arrives in their cities. The coveted Eras concert shirt is on display in short sleeve, long sleeve, and hoodie styles. The crowd is as eclectic as Swift’s fanbase—a mix of IU students and alumni, town folk, girlfriends with boyfriends, boyfriends with boyfriends, secondary school teachers, and college instructors, from as far away as California.

The bewildered dad of an IU student was among the first in line, instructed by his daughter to show up early and save a seat so that she could attend her morning class and still make the conference. “I have no idea what I’m doing,” he says, with a smile and a shrug.

I Bet You’ll Think About Me

Natalia Almanza, BS’21, the program and operations manager for the IU Arts and Humanities Council, steps to the podium, offering a warm welcome and a lighthearted challenge: “If you can’t find a single Taylor Swift song that you can relate to—I simply don’t believe you. You are a liar, and I hope you figure that out,” she says, with a mischievous smile.

The attendees laugh companionably as Almanza sets the tone. There will be no pretense of neutrality here. Many of the scholars speaking are avid fans—some even include the number of Swift concerts they’ve attended in their introductory bios—while others confess with apologies that they are not. Whether or not, all regard Swift as a cultural phenomenon who cannot be ignored.

Dr. Mary Fogarty, a professor of popular music and dance studies at York University in Toronto, offers the keynote address of the morning. Fogarty and her colleague Dr. Gina Arnold, professor and music critic at the University of San Francisco, co-edited “Taking Taylor Seriously” in 2021, a groundbreaking collection of Swift scholarship published in Contemporary Music Review.

Fogarty begins the conference by declaring its significance: “It is a great honor to be able to participate in an event that is both important and fun. When we dedicate a conference to a particular topic at a prestigious institution of higher learning, we are engaging in an act of legitimation and respect—in the act of, precisely, taking Taylor seriously.”

Observing what is available to study at universities is a way of determining what is valued in a culture, and what isn’t, Fogarty explains. “Forms of knowledge are legitimated at institutions such as this,” she says. “One of the ways we learn what matters in a culture is by seeing what is available to be studied in universities. But these venerable institutions have also been defined by what and who they exclude.”

Historically, she notes, the “realm of the popular” and the “realm of the feminine” have been determined not to matter. “These absences map with the historical exclusion of women, working class people, and racialized people in our society at large. Their interests, concerns, and pleasures were deemed not to matter, because for centuries they were not welcome in the university.”

While Fogarty emphasizes that much work remains to be done around gender, class, and race demographics in universities, she acknowledges that women in particular have made major strides toward inclusion. “Of course, this wonderful conference is one very loud sign of these changes,” she notes.

‘You Guys!’ Culture

Celebrity studies is a relatively new field, emerging in the early 2000s, as a branch of cultural studies focused on the complexities of fame and fandom. Many of the scholars gathered here are investigating the passionate relationship between Swift and her fanbase. Celebrities need fans, obviously for financial support, but also to build cultural capital. How does Swift, who lives a profoundly different reality from almost all other humans on the planet, cultivate fan relationships that feel so deeply personal?

Devoted fans desire to know both the real and ideal versions of their celebrity crushes. “Celebrities are combinations of media constructs and human beings. They are both ‘pixels’ and ‘bodies.’ And the combination of the real and the ideal is the source of our fascination,” Fogarty says.

Despite the fact that most of Swift’s fans will only ever experience her in digital formats, she communicates her humanity through the language of female friendship and empowerment. When addressing fans, she frequently uses the first-person plural, “we,” to describe her accomplishments, thereby implying: You and I … we did this together.

Swift often refers to her fans as “you guys,” a trope that enables her to speak to multitudes in the intimate language of “girl squad” friendship. Swift’s social accounts regularly shout out gratitude (“I love you guys!”) and, as poet and writer Madison Lazenby describes in her presentation, Swift fans respond with praise and sometimes critique.

“A fanbase is not technically a ‘movement,’ in the way Black Lives Matter is,” Lazenby says, “because it isn’t organized around a common objective. Yet Swift fans sometimes appear to possess movement-like power.”

The #SpeakUpNow letter is a famous example of fans working to repair their relationship with Swift. The fans demanded accountability after she was rumored to be romantically involved with an individual whose sexist and racist behavior did not align with values embraced by her fan collective.

The 2023 open letter to Swift—viewed more than 400,000 times on X (formerly known as Twitter)—demanded more from her than a mere apology: “Use your platform responsibly and intentionally. Advocate for inclusivity, celebrate diversity, and promote empathy and understanding.” After the letter was posted, the alleged relationship appeared to end abruptly.

Does fandom preservation require shared politics? It’s a question on the table, Lazenby says.

While some critics have suggested that Swift’s fandom preservation practices are calculated and tactical, talk to any avid fan and they will argue otherwise. The dance of mediation between Swift and her fans might be best characterized by advice Swift’s grandmother once gave her, now enshrined in the song “Marjorie”:

Never be so kind, you forget to be clever,Never be so clever, you forget to be kind.

Cats, Bracelets & Vibes

Managing a fanbase the size of Swift’s can’t be all “heart hands” and hugs. Jaime Gordon, a third-year student at Harvard Law School, demonstrates how Swift engages with intellectual property law to protect her artistic creations, while sometimes ignoring the law in order to cultivate fans.

In her presentation, Gordon foregrounds Swift’s savvy use of IP law, describing how she used a legal quirk in music copyright doctrine to record the much-celebrated “Taylor’s Versions” of her first six albums after a controversial business deal left her without creative and financial control. Swift, she notes, “is a trademark aficionado, registering wordmarks for all of her albums and songs, but also for discrete, seemingly obscure, aspects of her persona—such as the names of her cats,” she says.

Gordon is interested in aspects of Swift’s artistic output that fall outside the bounds of IP law, particularly the overarching themes and atmospherics that distinctly define each of her “eras.”

“Each of her albums exists in a complex story world of aesthetic and affective particularities—the namesake ‘eras’ that define her tour,” she explains. If you are a Swiftie, consider the folklore album’s portrayal on the Eras Tour stage, with its moss-covered piano and woodsy vibe, as an example of a Swiftian story world. These elaborate constructions are intrinsic to her personal aesthetic and brand, but they are not protected by law. “To put it simply … you cannot copyright or trademark a ‘vibe,’” Gordon says.

Legal theorists use the term “negative space” to define areas where innovation and creativity thrive beyond the borders of legal protection. “Fandoms are an important site of negative space IP, because fans create art that stems from intellectual property they don’t own,” Gordon explains.

The making and trading of the iconic Swiftie beaded bracelets, often spelling out song titles, lyrics, or cryptic acronyms related to Swift lore, is one example of “negative space” production inspired by Swift’s artistic property. “Despite the fact that the bracelets could be seen as infringing on Swift’s IP, she has endorsed the practice,” Gordon says. “There is something sanctified about it, rooted in core values shared by the entire Swift collective, namely, self-expression, attention to detail, and sentimentality,” she speculates.

Swift openly encourages fans to engage in the ritual, notably, in her song “You’re on Your Own, Kid,” in which fan creativity cycles back into Swift’s songwriting practice:

So make the friendship bracelets,Take the moment and taste it,You’ve got no reason to be afraid.

While some critics argue that every decision made by Swift and her team is commodified and monetized, Gordon is more measured. “It would be easy to paint everything Swift does with a single capitalist brush, given that her artistry is inescapably intertwined with the market. I find it more compelling to consider the juxtaposition between financial incentives and other motivations,” Gordon says. “The bracelets make the Swiftie experience feel more like friendship than fandom.”

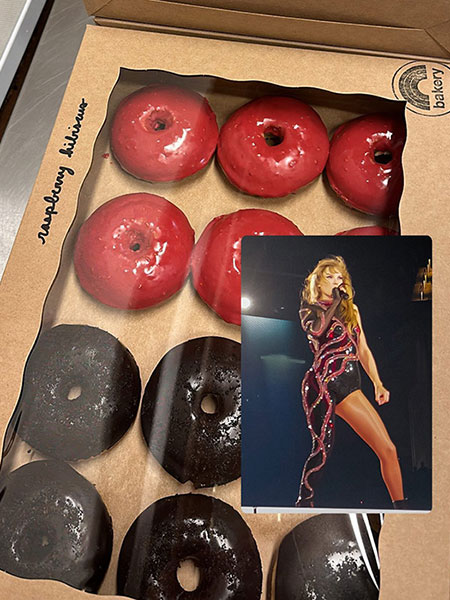

Karma Is a Donut

As people begin to trickle back from lunch, a public announcement is finally made about the donuts—boxes and boxes of them, supplied by Bloomington’s beloved Rainbow Bakery. They’ve been available in the upper lobby all morning, but the conferees are now made wholly aware of their presence. The most difficult part is choosing, because each box features a special flavor and color, themed to one of Swift’s albums. Reputation donuts are covered in dark, dark chocolate or deep raspberry hibiscus red, while Lover versions are dressed in see-through vanilla and accessorized with pink hearts. There are only a few remaining in the folklore boxes, so touching in their earth-toned, maple solitude.

The donuts are just one of the surprises Almanza and staff have dreamed up to ensure that the conference is both intellectually engaging and seriously fun. Along with scholars’ presentations and panels, her team has layered Swift-themed diversions into the weekend, including a scavenger hunt, a karaoke night, a dance party, and an arts market.

The IU Arts and Humanities Council is known for serious forays into popular culture, both celebrating it and treating it as a legitimate subject for scholarly discourse. A recent K-pop conference and the annual Granfalloon, a festival dedicated to Indiana author Kurt Vonnegut, are some recent examples.

Almanza says she is pleased to add Swift to the list, in part because she is the first woman to be centered in a major council event. “We haven’t talked about a strong female musician powerhouse in this way until now,” she says.

Feminist Awakenings

The theater is filling up again as conferees return from dinner, some holding Taylor-themed after-dinner cocktails, “Cruel Summer,” “Out of the Woods,” and others invented by the theater concessions staff.

Dr. Brenda Weber steps to the podium. She’s wearing a sparkly jumpsuit and a cat-ears headband in homage to Swift and to attendees who’ve come dressed in Taylor-esque regalia. The crowd whoops and applauds.

Weber is an IU provost professor, the Jean C. Robinson Scholar of Gender Studies, and the current director of the College Arts and Humanities Institute. Her list of scholarly accomplishments is long, including five books that explore themes of gender, sexuality, popular culture, celebrity, and selfhood. She teaches the popular IU course G225: Gender, Sexuality, and Popular Culture.

Weber, who calls herself a scholar and a Swiftie, tells the story of how she first came to admire Swift after viewing the 2020 documentary Miss Americana. In her presentation, Weber uses the film as a text to examine Swift’s evolution from aspirational child performer to embattled pop star to cultural power broker. The version of Taylor Swift who presides in Miss Americana is barely 30 years old, but “highly self-aware of her journey from ‘good girl’ to public feminist and activist,” Weber notes. “In Western culture, to be a ‘good girl’ is to be ‘passive, friendly, agreeable, and never difficult,’” she explains. “Even body size is implicated, with girls being pressured to be smaller, quieter—literally to take up less room.”

Swift’s evolving feminism is a form of maturation forged in part by the bitter experiences that often afflict women performing artists: relentless misogyny in media spaces and systemic sexism in the music industry. Like many others, Swift has been a victim of body shaming, sexual assault, and the ensuing public backlash when women speak in their own defense. Weber notes how Swift learned to navigate a toxic industry by refusing to hide her experiences from the public, speaking out directly in the media and in her songwriting.

In the early stages of her career, Swift maintained a public silence on politics and hot-button issues that might prove unpopular, even costly, to the broader financial economy of people depending on her success. Now Weber sees Swift as coming into her own, recognizing that her “good girl” stance was too constraining—too small for the enormous public figure she had become. Swift says it her way in Miss Americana, “It’s time to take the masking tape off my mouth. Like, forever.”

Throughout it all, Swift has remained fiercely focused on her creative endeavors. “Watching the artist’s alchemy as she turns nothing into something is one of the greatest forms of magic we can imagine,” Weber says.

What If I Told You I’m A Mastermind?

Swift’s creative output has earned her spectacular amounts of economic power, but Weber suggests that Swift possesses something equally, if not more, powerful. “Taylor is her own form of cultural currency,” Weber says. “She can get things done.”

The question of the moment, not just at this conference, but everywhere, all at once, is: How will Swift wield the colossal power—economic and cultural—she has amassed from her artistic labor?

Over the years, Swift has become more politically active: In 2018, she made her first public foray into politics, endorsing two Democratic candidates running in midterm elections in her home state of Tennessee. She also has spoken out against former President Donald Trump, both overtly and covertly on a number of occasions.

Last September, on National Voter Registration Day, Swift posted a nonpartisan call to action on her Instagram account, encouraging young people to register to vote. Move than 35,000 answered her call, boosting registrations by 23 percent during the one-day campaign.

Swift’s potential to affect political outcomes could extend beyond U.S. borders. Her success in encouraging youth to vote has captured the attention of European Union leaders as they prepare for a highly consequential parliamentary election taking place in June 2024. Taking note that Swift will be touring Europe this summer, Commission Vice President Margaritis Schinas made a public plea for Swift’s help in getting out the European youth vote. “I very much hope that someone from her media team follows this press conference and relays our request to her,” Schinas said at a press conference in Brussels on Jan. 10.

“She is aware of her power, and unapologetic about it,” Weber emphasizes. “[She has been] growing it and making it even larger, not only reinforcing her own ‘Americana Dream’ but changing the very contours of how we understand value.”

The lyrics of her song “Mastermind” ostensibly pertain to a romantic relationship, but it’s interesting to imagine them projected onto a wider social and political screen:

I laid the groundwork,and then just like clockworkThe dominoes cascaded in a line—What if I told you I’m a mastermind?

Whatever Swift does or doesn’t do, it’s unlikely we will look away anytime soon. The scholars and fans will be back for another Swift-packed day of conversation. And IU will go down in history as the place where Taylor Swift studies first converged in conference form, and, no doubt, it will remain a vibrant field of study for years to come.

Hey, you guys! This is only the beginning.

Written By

Deborah Galyan

Deborah Galyan, BA’77, is a freelance writer. She served as executive director of communications and marketing for the IU College of Arts and Sciences from 2012 to 2022.