Sound Connection

On the day it happened, Matt Hay, BS’99, MBA’09, had just returned to the office after hosting a celebratory lunch for his in-laws.

With their help, he and his wife, Nora (Lasbury) Hay, BS’99, had recently purchased an apartment with a rooftop deck in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood. He was dressed in a sharp suit and tie, as was the code at the Michigan Avenue advertising agency where he had landed after graduating from the IU Kelley School of Business.

Married less than a year, Matt and Nora had awakened that morning to the sound of the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun.” In Hay’s estimation, he had “married the most wonderful woman on the planet” and lived in the “best city” in the world.

Yet, a specter had followed him since early childhood. He had known it would catch up with him one day, but it must have seemed unimaginable on that spring day in 2004, as he tucked into a cab and headed back to work. At age 27, talent, good fortune, and charm had already given him an auspicious start to adult life.

Downtown again, he found himself riding the elevator with his manager, who began a conversation. For 21 floors, Matt struggled to follow his words, but the few fragments of speech he could hear he described as sounding like an “underwater trombone.”

Frightened, he called Nora. “Hey, I think it’s happening. I think this is it,” he said. But he couldn’t hear a single word of her reply. He fled the office and hailed another cab. Car horns and the clatter of L trains were muted as he headed home again. The driver’s words were indecipherable. He dreaded the thought of upending their lives, more for Nora than for himself.

In the hours that followed, Matt would lose his hearing entirely and awaken the next morning in a silent world. The specter, a genetic condition causing progressive hearing loss, had finally caught up with him.

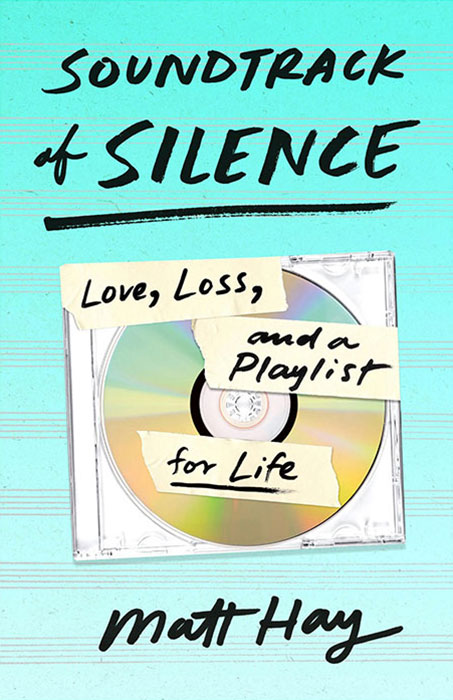

Hearing individuals are enveloped in layers of sound, even in their quietest moments. The complete absence of sound is almost impossible to simulate and equally hard to imagine. Matt has told his story in a memoir titled Soundtrack of Silence: Love, Loss, and a Playlist for Life. In the book, he brings readers as close as they might ever be to the experience of deafness, and offers a challenging question:

If the rest of your life had to be lived in silence, what sounds would you want to remember?

Fake It Till You Make It

As a child, Matt Hay thought everyone heard sound in the “scattershot bits and pieces” that constituted his normal, until the school nurse began conducting annual hearing tests. During the tests, he observed and copied his classmates’ responses and studied the nurse’s reactions for clues that allowed him to eke out an acceptable score.

In his teen years Hay adopted a “fake-it-till-you-make-it” strategy, projecting self-confidence he didn’t always feel.

Hay arrived in Bloomington in 1995 to pursue his undergraduate degree. He loved the social scene, football and basketball games, and the comradery of his fraternity brothers at Phi Gamma Delta, known as Fiji. He studied marketing and volunteered for Habitat for Humanity and the IU Dance Marathon. The delights and demands of college life made adaptive strategies even more crucial for managing his hearing loss.

“I turn into Jason Bourne,” he writes in the book, referring to the preternaturally vigilant character of thriller franchise fame, “assessing my surroundings, locating the quietest spot in the room, looking for the escape routes, and calculating how many steps it will take for me to get out of any awkward situation that might arise.”

As everyday sounds grew fainter, so did music, his constant companion since childhood. His infatuation began at home, listening with his parents to Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, the Eagles, and many more artists. He progressed through his rap years with MC Hammer, DJ Jazzy Jeff, and Snoop Dogg; on to the “aggressive years of manhood” with Lynyrd Skynyrd and U2; and finally to his college years, where music was a perpetual backdrop to life in the Fiji house.

The more he strained to hear, the more precious music seemed. As the specter of silence came closer, he began to commit a playlist of beloved songs to memory, preparing for a day when he would no longer be able to hear.

Hay knew and respected the fact that millions of people around the world thrive in Deaf communities, rejecting the idea of deafness as a disability. But he had grown up in the hearing world, with no connection to Deaf culture. He was willing to do whatever it might take to keep his hearing.

“The playlist would become my mental gymnastics,” he writes, “the workout I needed to keep my brain sharp and my memories from my hearing life alive.”

Reality Strikes

Back home for summer break, Hay’s worried parents urged him to get an audiology exam. The results were troubling, and he soon found himself lying on the deck of an MRI machine at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis.

He was diagnosed with a rare condition called Neurofibromatosis Type 2. More commonly known as NF2, the disorder is caused by mutations in the NF2 gene on Chromosome 22.

NF2 triggers the growth of noncancerous tumors within the nervous system, primarily in the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. The disorder has potentially life-threatening consequences.

Hay’s hearing problem was caused by tumors growing along the auditory nerves that relay information from the inner ear to the brain. He would need brain surgery in the near future to remove the tumors.

“At first, I thought this was good news,” he writes. “Now that we had the problem isolated, doctors could remove the tumors, and I would be ready to go; like splicing a broken wire, voilà, everything’s fine. I pitched that hypothesis to my doctors, who were kind enough not to laugh out loud at me.”

On the contrary, Hay was told the surgery itself could be tricky and unpredictable. Cutting around nerves in brain tissue can cause damage to other bodily systems. More striking news followed: the progressive nature of NF2 meant that new tumors would develop over time, and more surgeries would be needed in the future. And worst of all: surgery could not save his hearing. Sooner or later, he would be deaf.

“Hearing that news was like being hit between the eyes with a hammer,” he writes. “My mother’s soft hum; my father’s stories, the ones stuck on repeat; my fraternity brothers’ bad jokes; the throaty roar of a fast car; the ticking of a clock; the steady rumble of a train: all of it would be gone. And the music. Did this mean I would never hear Paul and Artie’s tight harmonies as they ran through the spice rack of ‘Scarborough Fair’? ‘Hello, darkness, my old friend’ indeed.”

‘Guinea Pig’

Despite his NF2 diagnosis, Hay returned to IU to finish his degree. Driven by an emerging personality trait he would later define as “irrational persistence,” he forged ahead, grateful to be surrounded by friends and close to family and expert medical care.

An IU adviser recommended he see Professor Nicholas “Nick” Hipskind, a beloved faculty member in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences.

Hipskind, who passed away in August 2024, took Hay under his wing and offered a proposal: If Hay would agree to serve as a practice patient for his audiology students, Hipskind would provide him with state-of-the-art digital hearing aids and follow-up care. Hay happily agreed to serve as a “guinea pig” once a week.

Wearing his hearing aids outside the clinic for the first time, Hay felt as if he had been “dropped in a noise machine. … I heard birds chirping, kids talking, bike tires humming against the sidewalk. … Everything hit me at once.”

The hearing aids proved essential to his academic success at IU. “I don’t think I could have graduated without them,” Hay says.

Despite the relief he felt, Hay had to manage his optimism. Even this cutting-edge technology would one day fail him. As his time at IU drew to an end, Hay was often caught in pendulum swings of emotion. Some days he was positive, having resisted the idea that his future was determined by NF2. Other days he felt despair.

Then he met Nora Lasbury.

Millennial Meetup

The most perplexing thing about Matt meeting Nora was figuring out how it was possible that they hadn’t met sooner. Both were seniors with friends in common, not the least of which was Hay’s roommate.

“I first saw Nora in room 17 of the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity house as she studied for an organic chemistry exam with my roommate,” he writes. The fact that she was helping several of his smartest friends with their chemistry homework made a strong impression. “Until that moment, I’d never understood what having your breath taken away meant.”

They saw each other once more at a graduation party, but there was little chance to talk. Matt moved to Chicago to begin his new job as a marketing professional. Nora, biology degree in hand, headed to Indianapolis for her first year at the IU School of Medicine.

Six months later, in the final hours of 1999, Matt spotted Nora in a Chicago pub. It was packed with recent IU grads who had reunited to celebrate a once-in-a-century New Year’s Eve. In a rom-com-worthy maneuver, he made his way through the crowd, timing his approach so that he “just happened to be” standing next to her at the perfect moment to welcome the new millennium with a kiss. From then on, it was Matt and Nora.

Soon they were dating, traveling between Chicago and Indianapolis, when their schedules allowed. Matt relied on Hampton Comes Alive, a six-CD collection by Phish, to distract him as he forged through rush-hour traffic to the Skyway. When summer arrived, Nora came to Chicago more often.

“Two healthy people in love: What could possibly go wrong?” Matt writes. The answer came in the form of a nagging pain in his neck.

Collateral Damage

Matt had been open with Nora about his condition from the beginning. She knew as much as he did about NF2, possibly more, given her science and med-school courses. They put their summer plans on pause and scheduled Matt for an MRI. They stood side-by-side as doctors displayed the image of a three-inch tumor near the base of his brain and described how it was clogging the flow of spinal fluid. He was in surgery within days.

Matt woke up in the recovery room, unable to move his legs. As doctors had once warned, the surgery had caused collateral damage to nerves in his lower extremities. Removing a spinal cord tumor, he writes, is like “digging the last Pringle out of a can: messy, imprecise, and uncertain.”

Nora, after talking with the doctors, gave Matt the news: “We think you will be able to walk again.”

The monotony of recovery was tempered by the joy of being together with nothing much to do. Nora brought Subway sandwiches to the rehabilitation facility each day as Matt slowly regained his ability to walk. They spent hours watching old movies and eating popcorn. They put Matt in a wheelchair and sneaked out on jaunts around the neighborhood.

“This was happiness,” Matt writes. “This was love.”

Matt regained his mobility and returned to work within a few months—a near miracle, given that his complications could have put him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Just under a year later, they celebrated by running a marathon together.

On a January night in Bloomington, Matt proposed to Nora. In rare 60-degree weather, they strolled through the Sample Gates to the Rose Well House. Matt set the scene with candles and a battery-powered boombox.

“We slow-danced like high schoolers,” Hay writes. “Then I got down on one knee, no small feat given that I hadn’t been able to walk five months before.” They married in October 2002.

‘Matt, Can You Hear Me?’

On the day it happened—the day Matt lost his hearing and rushed home from the office to see Nora—he felt miserable, fearing he would soon be profoundly deaf, and knowing she would be entangled in every hardship to come.

She was waiting for him on the landing. As he approached, she made the ASL sign for “I love you.”

“Seeing her hit me like a wave. … As always, all she thought about was me, my well-being and my feelings,” he recalls. “I had to catch myself to keep from crying, not at my loss but at my good fortune.”

Matt read her lips as she reassured him that they had done their homework: researching treatments and learning sign language. “Matt, we’ll deal with this and be OK,” she said.

Together, they decided Matt should pursue an auditory brainstem implant, or ABI. The surgical implant, combined with a wearable processor, made it possible to bypass damaged auditory nerves in the cochlea and inner ear, sending sound signals directly to the brain.

Matt was warned about complications and was told not to expect too much from the ABI technology itself. His hearing would be mostly limited to “life sounds,” such as smoke alarms and oven timers. The subtleties of speech would remain far more elusive. “Jackhammer” and “gravel truck” were words the doctors used to describe the distorted quality of the sounds typically produced by the ABI.

And Matt would need to heal for three months before he could return to the institute to have his ABI activated. Only then would he know if the procedure had worked.

Matt took the warnings in stride. He didn’t mind, as long as he heard something.

About six months later, in October 2004, Matt and Nora traveled to the House Institute, a leading-edge center for hearing disorders in Los Angeles, where surgeons removed the benign tumors that had destroyed his hearing. Then, working with less-than-complete knowledge of the brain, they attached an array of twelve electrodes to corresponding audio sensors in his brainstem.

Matt awoke from surgery to face a gamut of serious complications, including the predicted facial paralysis and balance issues that would take many months to resolve. The doctors were optimistic. For a time, Matt struggled to share their point of view.

Three months later, they returned to L.A. for the activation of the implant. The room was charged with emotion as Nora watched the audiologist attach the external sound processor to Matt’s implanted electrode array. Instantly, Matt heard the harsh rumble of the audiologist’s voice, and then Nora’s voice, staticky and strange.

“Matt, can you hear me?” The words were unclear, but he could hear his wife again. “I love you,” Nora said, speaking and signing.

“I love you, too,” Matt said. “It’s not exactly crystal clear, but it’s a start.”

Irrational Persistence

The ABI—combined with their “lip reading, sign language, and charades”—made Matt and Nora’s daily routine more manageable.

But several years after his surgery, Matt’s hearing had not significantly improved. Sounds and speech remained highly distorted.

Anxious to push the boundaries of the technology, he reviewed the ABI research: There were no rehabilitation protocols to help patients improve their comprehension, scant patient histories, and little evidence that comprehension could be improved. Even ABI specialists admitted they didn’t completely understand how the device worked.

Matt began thinking about the playlist he had created over the years, wondering if those familiar songs could become the key to translating the sounds his ABI was hearing into the language his brain understood. He dusted off the CD that contained an old playlist with its handmade label, “Songs We Like,” and loaded it into the car disc player.

He began a diligent daily practice of matching the song lyrics he had memorized to the corresponding sounds his ABI produced. For three years, he listened to those same 12 songs, over and over again.

“Instead of accepting that my ABI would always struggle to tell my brain how things sound, my brain would now tell my ABI how things were supposed to sound, based on what I already knew,” he explains. “John, Paul, George, and Ringo would become my translators.”

Matt gave a name to his relentless determination: irrational persistence. “I’m going to keep working on this every day, with no confidence that it will get better,” he vowed.

Then one day, Nora and Matt were in the car, listening to music. Suddenly Matt heard a line from a song: “Johnny, what you doin’ tonight …”

“Is this ‘Crazy Game of Poker’ by O.A.R.?” he asked. “Yes,” she confirmed.

Thrilled, they pulled off the road for a hug. For the first time in years, Matt had actually heard and recognized a song lyric.

“Not a song in my head; this was music playing at the moment in real life,” he writes.

It was the incentive he needed to keep working at a painstaking process, one that would take many more years as he trained his brain to hear sound in a way that humans had never heard it before.

Sharing the Story

Twenty years into his journey, Matt’s speech understanding has soared from 20 percent to 96 percent, making him a dramatic outlier among ABI recipients and a valuable subject for further research. His intuitive sense that music could help with speech understanding was extraordinarily prescient—music therapy is now considered a highly effective tool for improving auditory function.

Today, Hay’s passion is helping people with hearing loss. He serves as U.S. director of advocacy in the research division of a global biopharmaceutical company, where he works with patient groups representing individuals with hearing-related diseases. He also serves on medical advisory boards and has lobbied in Congress for additional research and funding.

But perhaps his most powerful act of advocacy is telling his story. His memoir, Soundtrack of Silence: Love, Loss, and a Playlist, which arrived on bookshelves in early 2024, has led to a series of high-profile media interviews, including a poignant conversation with National Public Radio host Mary Louise Kelley, who is also hard of hearing.

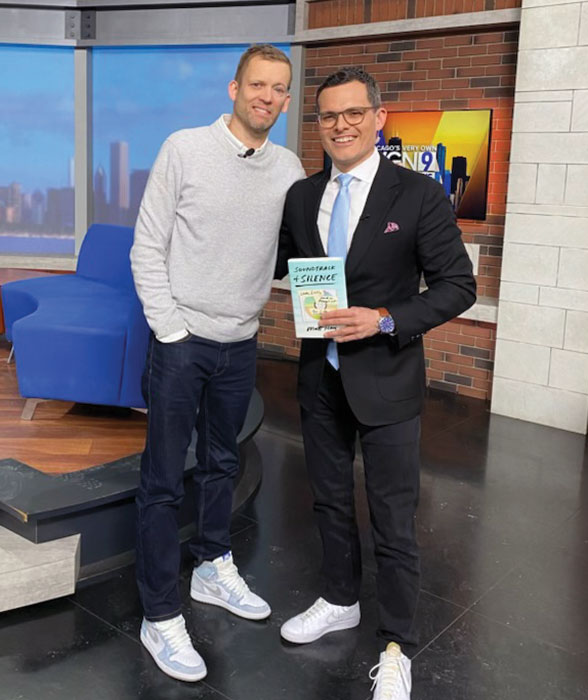

He was also interviewed on television station WGN in Chicago by host Dan Ponce, BS’99, his good friend and fraternity brother, and he recently gave a talk as part of TEDxWrigleyville, just a few miles from the Chicago neighborhood where he and Nora first shared their lives. Rights to his book have been optioned by Hollywood actor Channing Tatum and Paramount Pictures for potential adaptation to film.

In Matt’s case, irrational persistence wasn’t so irrational, after all.

His speeches and his book exude that spirit of persistence, as well as a profound sense of gratitude and love. As he writes:

“Unfortunately, life will go sideways on you at some point. It’s not a question of if; it’s when and how bad it will be. But in those tragic times, when bad news falls over you like a dark cloud, there are glimpses of beauty, inflections of love that penetrate beyond the ordinary. There is, in hardship, a depth and richness inside a relationship that you might never have otherwise found.”

Written By

Deborah Galyan

Deborah Galyan, BA’77, is a freelance writer. She served as executive director of communications and marketing for the IU College of Arts and Sciences from 2012 to 2022.