One hundred years ago, a section of Tulsa, Okla., called Greenwood, more commonly known as “Black Wall Street,” was destroyed by a hostile white mob armed with guns, knives, and other weaponry. Businesses and homes in this thriving community were burned to the ground. Over 300 Black people were killed.

The event was erased from the formal history of Tulsa and, until recently, the American consciousness. However, one of Greenwood’s most successful business leaders of the time, J.B. Stradford, with links to the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, provides, primarily through his 1935 memoir, his personal account of the terror associated with the assault on his community.

The narrative has been passed along by his great-grandson, Cornelius E. Toole, a fourth-generation lawyer in the Stradford family and a circuit court judge in Chicago. Toole recounted his great-grandfather’s account in a news release that he prepared in 1996 for the archives of Oberlin College, where his grandfather completed his undergraduate studies. Toole was 2 years old when J.B. Stradford died, but he was so inspired by his memoir that he reached out to the McKinney Law School for verification of his great-grandfather’s connection to IU.

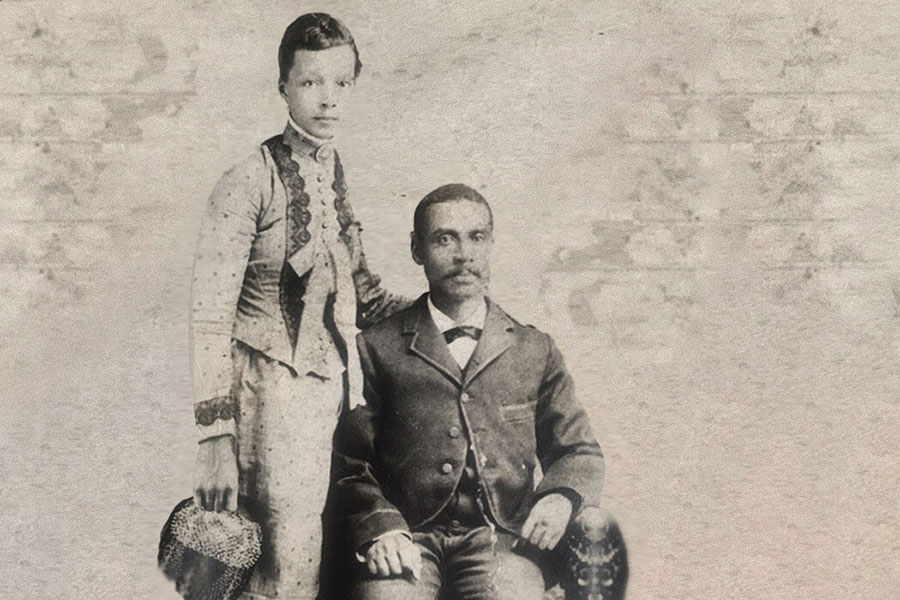

J.B. (John the Baptist) Stradford was born in 1861 in Kentucky. After Oberlin College, he attended Indianapolis College of Law and graduated in the class of 1900. In his memoir, Stradford spoke of lectures on constitutional law presented by former U.S. President Benjamin Harrison. The Indianapolis College of Law later merged with the American Central Law School and became the Benjamin Harrison Law School. In 1936, the Benjamin Harrison Law School merged with the Indiana Law School, and, in 1944, the school became part of Indiana University, making all previous graduates alumni of Indiana University School of Law, now the IU McKinney School of Law. It is also reported in the Indianapolis Journal of July 2, 1900, that Stradford was admitted to practice law in Indiana.

Stradford moved to the Oklahoma territories seeking opportunities related to the discovery of oil. Although he did not profit from the oil boom, Stradford was able to join other Black families who were building up “Little Africa,” which was later known as Greenwood.

As a budding entrepreneur, he borrowed money to build the 54-room Stradford Hotel. With segregation laws in place, all Black musicians and celebrities visiting the area stayed at the Stradford. Other establishments in Greenwood, including the Stradford Library, carried his name.

As a civil rights pioneer, he unsuccessfully challenged the “separate but equal” doctrine of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision, after he was ousted from the railroad facilities while traveling through the state to attend his son’s high school graduation in Kansas.

Stradford was also known as an outspoken critic of lynching. In May 1921, he led a protest against the arrest and threatened lynching of a Jewish man by a white mob. Approximately a week later, his activist mindset led him to organize a group of Greenwood men to advocate for a young Black man unfairly charged with assaulting a white woman. The assault charges were eventually dropped against the young Black man because there was no evidence of a crime.

White citizens, however, were incensed by the advocacy, and retaliation against the citizens of Greenwood ensued. Toole used J.B. Stradford’s memoir to provide this account of the May 1921 events:

“The (Stradford) hotel was bombed from an airplane. There were two airplanes in Oklahoma at the time, one owned by the governor of Oklahoma, and the other owned by Sinclair Oil Company. Sinclair’s plane was accounted for, but the governor’s plane could not be accounted for. J.B. was arrested, as stated herein, and placed in custody. His son, C.F. Stradford, drove to Tulsa and filed the “Great Writ” (of Habeus Corpus), which probably saved his life and enabled him to be released. The story in my family is that he was sneaked out of Oklahoma on street cars, going from town to town, and state to state until he came to Chicago. He never returned to Oklahoma and lost all of his real estate and personal property and business.”

Toole served as the official representative of the Stradford family in 1996 when Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating presented a proclamation to the family along with an honorary executive pardon. Keating apologized to the Stradford family at the Greenwood Cultural Center, stating, “It is regrettable that we have to come together to recognize an embarrassment, a historic event that never should have happened.” During the ceremony, Tulsa County District Attorney Bill LaFortune requested that Judge Jesse Harris of the district court formally drop all charges against J.B. Stradford. So, after 75 years, Stradford was officially exonerated and no longer a wanted fugitive.

This story was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of The McKinney Lawyer.

The IUPUI McKinney School of Law held a commemorative event to recognize J.B. Stradford in September 2021. Watch the replay.