Philadelphia in the 1960s. The courtroom of Juanita Kidd Stout. If you were a criminal, this is not where you wanted to be.

Judge Stout, JD’48, LLM’54, LLD’66, was noted for her firmness, and she was particularly incensed by ignorance, according to news accounts of the time. Ignorance, she believed, was an underlying cause of crime, especially for those who had dropped out of school and hadn’t learned to read or write.

And to those less than truthful?

“I take a dim view of anyone who lies, no matter what the situation,” she once said to a defendant who had misled her. “If at the point of trial, you are still trying to deceive, it is proof positive that rehabilitation has not begun.”

For those who were remorseful and committed to positive change, however, Stout — whose first career was as a teacher — could be accommodating.

“She was tough on gang violence and let them know [they] could have a better life without fighting,” Tyrone Stevens Drummond, whom Stout had mentored since he was a teenager, once told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “She wanted to let children know you need to learn to read and write and speak well, and then you can get a job.”

So, with the right attitude, maybe her courtroom was where you wanted to be. She offered a path out of criminality.

Stout — who was small in stature; she reportedly sat on three pillows while presiding — was on the bench for more than four decades. She was the first Black woman in the country to win an election to a court of record, in 1959, and the first to serve as a state supreme court justice, in 1988.

With her trailblazer status and no-nonsense approach, she was a regular media subject, both in Philadelphia and nationally. Ebony magazine featured her in its March 1960 issue (titled, reflecting the times, “Philadelphia’s Lady Judge”), and Life magazine profiled her in July 1965 with “Her Honor Bops the Hoodlums.”

Upon her death, in 1998, The New York Times and numerous newspapers around the country published obituaries that chronicled her life in glowing terms.

Indiana University took notice, too: an honorary degree in 1966; a feature story in this magazine in 1969; induction into the Maurer School of Law’s Academy of Law Alumni Fellows in 1986; and, in 1992, the Distinguished Alumni Service Award, the highest honor given by the university to an alumna or alumnus.

Now, more than 30 years after her death, her accomplishments are again being highlighted. As the first Black woman with a professorship named in her honor at IU, she is, again, a trailblazer.

“She needed to be recognized in a way that would keep her story in front of the law school community,” says IU Executive Vice President and IU Bloomington Provost Lauren Robel, JD’83, who once served IU as dean of the Maurer School of Law and gave the lead gift in support of the professorship. “It’s an important part of our history, but it’s also really, really important that our students — all of our students, whether they’re African American or whether they’re Hispanic or whether they’re white, whatever their background is — understand that people of her talent came out of our law school in her shape and form.”

Early Promise, Advanced Degrees

Juanita Kidd Stout’s story was marked by excellence from an early age.

Her parents were school teachers in Oklahoma. Juanita was born there in 1919, and by age 3 they had taught her to read. She entered the third grade at age 6. A top student through grade school and high school, at age 16 she was off to college in Missouri. Ultimately, she studied piano and voice at the University of Iowa, from which she earned her undergraduate degree — at age 20.

After college, she taught music at the grade school and high school levels for a time back in Oklahoma. During World War II, she moved to Washington, D.C., and found work as a secretary at a prominent law firm. The job, it seems, set her on a path to an accomplished legal career.

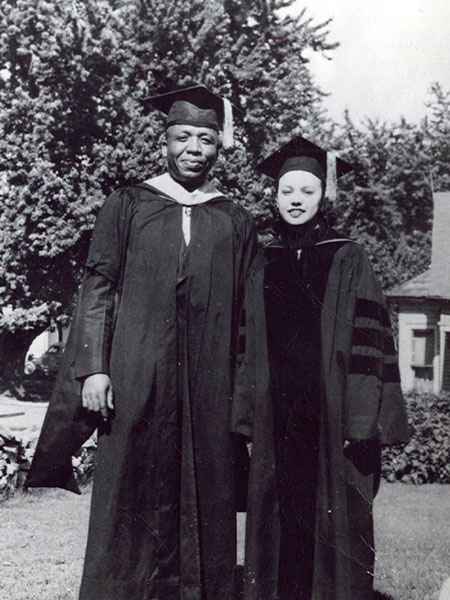

She and Charles O. Stout, MS’48, EdD’50, married in 1942, and they made their way to IU after the war. While she earned her two law degrees, he pursued his master’s and doctorate degrees in education, on his way to becoming dean of mechanical engineering at Maryland State College.

Her years at IU included time as a graduate research assistant for Professor Frank E. Horack Jr., who served on the law school faculty from 1935 until his death in 1957 at age 50. Stout described him as “a warm personality, a genuine friend, [and] an inspiring teacher.”

Overcoming Obstacles

“[Justice Stout] came from a deeply segregated world,” Robel says. “[While] learning was hugely important in her family, the notion that someone of her background would have the analytical ability and the command of elegant language [was] just not within the contemplation of the people who stood in her way as she tried to get an education and then a legal education.”

Stout finished her last year in the educational system the same year, 1954, that the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision on Brown v. Board of Education, which made unconstitutional the practice of racial segregation in public schools.

When she was a girl, racial distinctions were foreign to Stout.

“[My parents] never said ‘colored’ or ‘white’ to me,” she said. “Until one day, when I was little, a man came to the door. I went and told Mama a man wanted to see her and she forgot for a minute and said, ‘Is he white or colored?’ I said, ‘Mama, I don’t know.’”

But, by the time she was ready for college, Stout faced a segregationist practice in her home state of Oklahoma. The reason she had gone to Missouri to study was because Oklahoma did not have an accredited college that would admit a Black woman.

Later, contemplating law school in the 1940s, she again was limited in her choices.

It wasn’t until 1950, when Stout was well into her study of the law, that the Supreme Court — through two rulings, McLaurin v. Oklahoma State and Sweatt v. Painter — ended the practice of “separate but equal” in graduate and professional education.

Her race was one factor; her gender was another.

In her time, the percentage of women working as active lawyers was extremely low. According to a 2019 report by the American Bar Association, from 1950 to 1970 only three percent of all lawyers were women. (In the decades since, that number has risen: eight percent in 1980; 20 percent in 1991; 27 percent in 2000; and 36 percent in 2019.)

Reflecting that reality, Stout once said: “I think I always wanted to be a lawyer, but I didn’t know for a long time that girls could be lawyers.”

Success in Philadelphia

Despite the obstacles, she did, indeed, become a lawyer and soon set up shop in Philadelphia. Within a couple of years, she joined the city’s district attorney’s office.

In the 1965 Life article, she referred to her time in the DA’s office as “golden days,” despite describing herself as a “workhorse” lawyer, hired to plow through a backlog of cases.

“Those were the happiest days of my life,” Stout said. “I had never written a brief or made an appellate argument, and I was getting up at four in the morning every day—I mean every day, Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays—to study and work and do research.”

She was promoted within the office, and soon after, in 1959, she was accomplished and well-known enough to be appointed by the governor to temporarily fill a vacant seat on the municipal court. Two months later, she won an election to fill the vacancy. She was the first Black woman in the country to win an election to a court of record.

During her 10-year tenure on the municipal court — and subsequent 20-year tenure on the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas — she developed her reputation for being a tough but fair judge.

Along with the firm approach — true to her experience with the positive power of education — she would always include some form of learning into the requirements of probation.

In a Philadelphia Tribune article, a close friend said, “She never stopped promoting education. Everyone who passed her way got an earful about the importance of education.”

In 1988, Stout made history again when she was appointed by the governor to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. She became the first Black woman in the country to serve on a state supreme court.

Only a year later, she stepped down because she had turned 70 — the mandatory retirement age. She returned to the Court of Common Pleas and served there as a senior judge until her death in 1998.

Former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, who, early in his career, tried a number of cases before Stout, said in 2012: “The thing that was so important about Judge Stout was that she would have been a brilliant judge at any level — trial court, Superior Court, Supreme Court — whether she was a man, whether she was white, Asian, Hispanic.”

Recognition, Then and Now

In her lifetime and after her death, Stout was lauded for her accomplishments. Just as IU had, the University of Iowa named her a Distinguished Alumna; in 1988, she was made Justice of the Year by the National Association of Woman Judges; and, in 2012, the Criminal Justice Center in Philadelphia was renamed the Justice Juanita Kidd Stout Center for Criminal Justice.

When Stout visited Bloomington in 1992, Robel (then a Law School faculty member) spent the day with her.

“I remember when I met her, she was in a big chair in the lounge in the [Indiana Memorial Union],” Robel recalls. “She was a tiny woman. Tiny, composed. There was a stillness about her that led to every word that came out of her mouth [feeling] deeply considered. I had no idea at the time the way in which she thought of language as a tool of power for people like her.”

There were many other accolades, but perhaps none as validating as induction into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame. Her home state, decades after its system had forced her to leave to pursue a college education, had honored her as one of its heroes.

And now the professorship at the IU Maurer School of Law.

The dean of the school, Austen Parrish, said in a statement that professorships are key in retaining top faculty, improving the academic environment, and attracting the best students.

Speaking specifically, he said, “It will be a tremendous honor for a faculty member to be named the Juanita Kidd Stout Professor of Law.”

Jeannine Bell, Richard S. Melvin Professor at the Law School, says that students — particularly those who have been historically underrepresented — can draw lessons from the professorship.

“They need to know that they are stepping into a legacy, and a legacy that looks not just like most of the people on the walls at the Law School, but a legacy that also looks like them,” she says. “[This professorship] will be helpful to them by showcasing [Stout’s] difficulties, and what she did [in] a troubled time will help them think about what are they going to do [in] the troubled times that they face.”

Although modest, Stout did acknowledge her place in history. “Looking back, I guess that I have [done historic things],” she told the Philadelphia Tribune, “but when I was doing these things I did not know that I was being a pioneer. I just did them because I wanted to.”

Justice Stout’s Memories of IU

In 1970, to celebrate its 150th birthday, Indiana University produced a publication titled IU Sesqui ’70, which was distributed in newspapers throughout Indiana and parts of Kentucky. In it, Juanita Kidd Stout contributed — along with Hoagy Carmichael, LLB’26, DM Hon’72, and other IU notables — to the “The IU I Remember” section. Stout’s piece, below, focused on one of her law professors.

“Go Fishin’!” These two words bring fond memories of one of Indiana’s great law professors the late Frank E. Horack Jr. (He wrote his name with no comma before “Jr.”)

A warm personality, a genuine friend, an inspiring teacher, and an avid fisherman, Mr. Horack parked the “Little Green Hornet,” a vehicle of great antiquity, behind Maxwell Hall while inside he imparted principles of agency and maxims of statutory construction to students who awaited his coming with eagerness. Frequently, he punctuated his lectures with the imperative “Go Fishin’!” which meant various things, all well understood, depending on the context in which it was used and the inflection and tone of voice in which it was said.

The day before my last examination in law school, Mr. Horack asked me to work for him as a graduate research assistant the following year while I pursued the LL.M. degree as my husband completed his doctorate. The opportunity to work for this great legal scholar whom I admired so much overwhelmed me. Then came the next day and that final exam in Mr. Horack’s legislation class.

Because of my intense desire to do well on my future employer’s examination, I was filled with anxiety and the quality of my answers did not satisfy me. When the examination was over I envisioned failure, a lost opportunity, and, most of all, the embarrassment of my first failure, and that before Mr. Horack. I went home, broke into tears, and cried almost all night.

The next morning my husband, Charles Otis Stout, who is a great tease but who knew nothing of Mr. Horack’s favorite expression, went to the campus and, quite by accident, ran into him. When he returned home Otis said, “I saw Mr. Horack a few minutes ago and told him you were worried about his exam.” This brought another torrent of tears as I retorted, “How dare you tease me like this!” Those tears ceased to flow and my face broke into smiles, however, when he said, “Mr. Horack sent you a message — ‘Go fishin’!’”

P.S. The grade was “B.”

This story appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of the IU Alumni Magazine. It is now part of our Black History Month series, IU’s Black History Makers.