One has a lumberjack license. One spent years cake decorating. One finds symmetry between art and hip-hop.

The common thread between these three individuals? They’re artists who have called IU home. These folks—and other notable alumni artists profiled in this story—have exhibited work across mediums in museums around the world.

Take a look.

‘Girl With Big Dreams’

When Katy Lengacher, BAJ’10, was a teenager, she traveled to the Netherlands with her father. As a young tourist with a penchant for art, she remembers visiting museums and seeing works by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Johannes Vermeer—the Dutch Masters.

In May 2023, Lengacher, who is now a professional photographer, returned to the Netherlands. This time, she was there to see her artwork on display in a museum.

Lengacher’s portrait, “Girl With Big Dreams,” was selected for exhibition at the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague. Though inspired by the style of Vermeer’s “Girl With a Pearl Earring,” several elements of her work differ. The girl in Lengacher’s photograph wears a Saturn earring, holds a telescope, and is seen against a starry background.

“I was aiming to make it almost like a feminist critique of that painting,” Lengacher says. “She’s [unlike] the girl with a pearl earring—the focus isn’t on what she looks like and what she’s wearing. She is a girl with big dreams.”

Lengacher’s model was her daughter, Sagan, who is named after astronomer Carl Sagan. When creating the portrait, Lengacher purposefully used imagery reflecting her namesake.

Vermeer’s iconic painting has long been a favorite of Lengacher’s. As a 12-year-old girl, the artwork came to life for her after reading the historical fiction novel Girl With a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier.

Serendipitously, Sagan, 12, got to see her image hanging in the very same room as "Girl With a Pearl Earring" when the mother-daughter duo traveled to The Hague.

"It was absolutely surreal,” Lengacher says.

‘Cantos Familia’

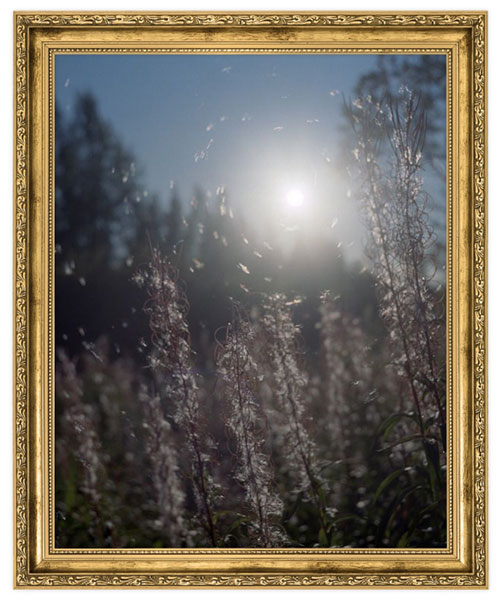

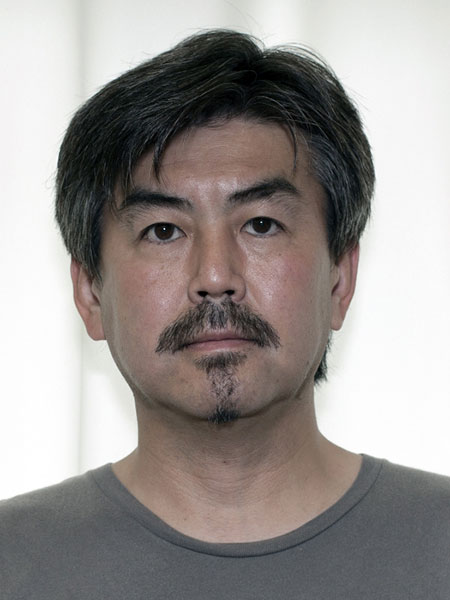

Photographic artist Jun Itoi, BFA’97, remembers seeing Robert Capa’s “The Falling Soldier” when he was in high school. He points to Capa’s photo, which was taken during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, as what sparked his interest in photography as a career.

"He took the photograph right as a soldier got shot and was falling down. That one picture was so strong," he says. "To me, photography is poetry."

Originally from Japan, Itoi decided to study photojournalism in the U.S. and enrolled at Vincennes University. When his interest shifted toward fine arts, he transferred to the Herron School of Art and Design at IU Indianapolis. While there, Itoi took photos for The Sagamore, the student newspaper, which is now called The Campus Citizen.

“I was taking pictures in black and white film, processing film, printing, cutting, and pasting it on paper," Itoi says. “It was fun, hands-on, tactile work.”

Looking at his photography portfolio, you’d think that Itoi was always a full-time artist, but that couldn’t be further from reality. After graduating college, he worked in the newspaper industry; spent a year teaching at IU Bloomington; worked at Morgan Stanley in Japan for the better part of a decade; and eventually earned his lumberjack license. Yet his passion for photography never waned.

His highly acclaimed project "Cantos Familia" was exhibited for the first time in 2010. It would appear around the globe 14 more times over the next ten years, including at the Kurumaya Museum of Art in Oyama, Japan; the National Art Center in Tokyo; and Pictura Gallery in Bloomington, Ind.

"Cantos Familia" consists of more than a dozen dark and lyrical photographs taken by Itoi in the forests of Finland, focusing on the light there. The images were taken shortly after his father died by suicide.

"He committed suicide by hanging himself on a tree in a forest near my parents’ home," Itoi shares. "We did not realize he was suffering that much from depression, but my mother found out about it when he disappeared leaving a note behind. We searched five nights and four days until we found him. From this experience, the existence of forest has become important to me."

“Ananse Ntontan (Wisdom)”

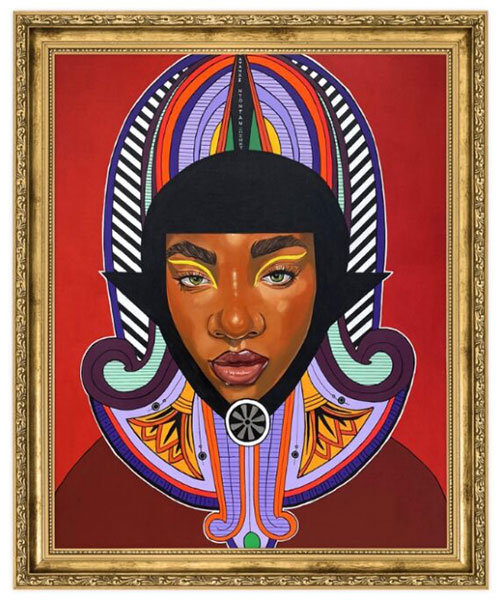

Visual artist Tasha Beckwith, BFA’06, showed artistic promise when she was in grade school. Little did her teachers know, she’d one day be painting some of Indianapolis’ most iconic murals and showcasing her artwork in museums across the Midwest.

Beckwith describes her work as “portraiture that specifically deals with Black people as the subject matter in an Afrofuturist style.”

"After my undergraduate studies, I thought I knew what kind of art I wanted to make. But one day, as I was reviewing my work, I felt like it wasn’t good enough and wasn’t going to have the desired impact," she explains in an interview with the Herron School of Art and Design. "So, I spent a lot of time researching and looking at other artists’ work that I admired, taking note of which elements worked best and incorporating some of those things into my own pieces, which caused the work to evolve into what it is today."

Oil on canvas and large-scale public art projects are Beckwith’s staple art forms.

Her public projects have ranged from traffic box art to an 11-foot tall and more than 75-foot wide mural depicting entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker, which is a fixture at the Indianapolis International Airport.

"I love public artwork and that it’s accessible to everyone because it’s not contained within four walls. I also love that Black people get to see themselves represented in these large-scale works," Beckwith says. "Getting to paint such a legend of the city [Madam C. J. Walker] on such a large scale meant a lot to me."

Over the past five years, Beckwith’s paintings have been displayed three times at the Museum of Science and Industry for Chicago’s annual “Black Creativity" exhibition. The first time was in 2019 when her piece "Moon Sister" was selected. In 2023, she showed two oil paintings titled “Ananse Ntontan (Wisdom)” and “Bi nka Bi (Peace).”

“These paintings are my interpretation of what an afro futuristic African queen looks like,” she says. “Each queen represents a different Adinkra symbol—African symbols that represent different principles.”

Ananse Ntontan translates to a spider web and represents wisdom and creativity. Bi nka Bi translates to “nobody should bite the other” and represents peace, harmony, and forgiveness.

“When people view the paintings, I hope they strive to have more wisdom and peace in their daily lives,” Beckwith says.

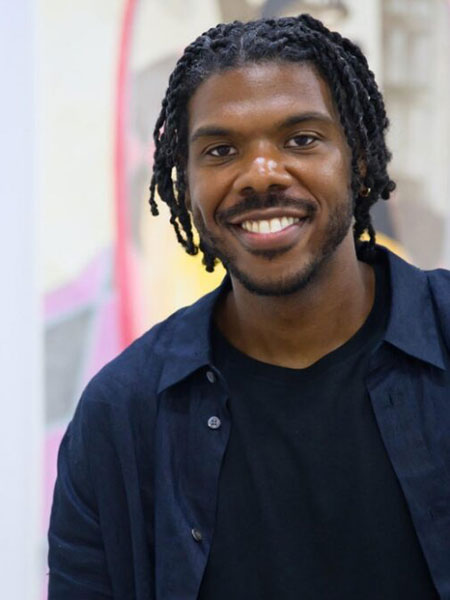

‘Red Act 2’

As a child, Joshua A.M. Ross, BFA’15, spent time flipping through his grandmother’s photo albums and watching his mother style hair for a living. He points to these experiences as two catalysts for his creative life.

“When I looked through photo albums, it just felt like I had access to a part of life that was not available to me in the present,” Ross says. “And when I watched my mom do hair, that was the first time I saw someone occupy a creative space.”

Ross’s grandmother placed a lot of value on photography and “passed the camera torch” to him.

“I think it had something to do with her only ever having one picture of her mother,” he says. “She took tons of pictures and noted the details methodically.”

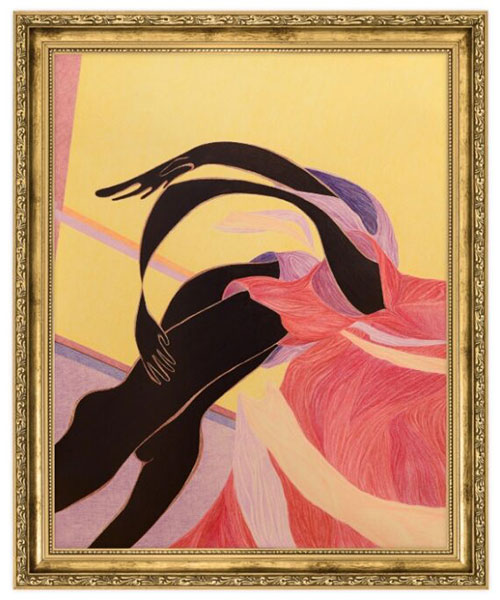

Ross, who studied photography at Herron, describes the art form as his “anchor medium.” It formed the way he thinks about visual art and the language he uses to describe it; however, his artistic tool of choice is no longer a camera, but often colored pencils.

Ross’s art is known for its texture and use of layered color to depict the human body. These elements were particularly present in the five colored pencil and graphite drawings he showed at the Aspen Art Museum from December 2022 to April 2023.

The museum described the exhibition, “Shadow Tracer: Works on Paper,” as delving “into the inherent experimental spirit of drawing,” with Ross’s artwork showing bodies in ecstatic movement.

The drawings blossomed from a series of sketches of a person dancing in a studio with wall-to-wall mirrors.

“I decided to zoom into the parts that heightened the fact that dance was happening, which in this scene were fluttering cloth and delicate lines leading to points sandwiched with the mirrors,” Ross says of "Red Act 2."

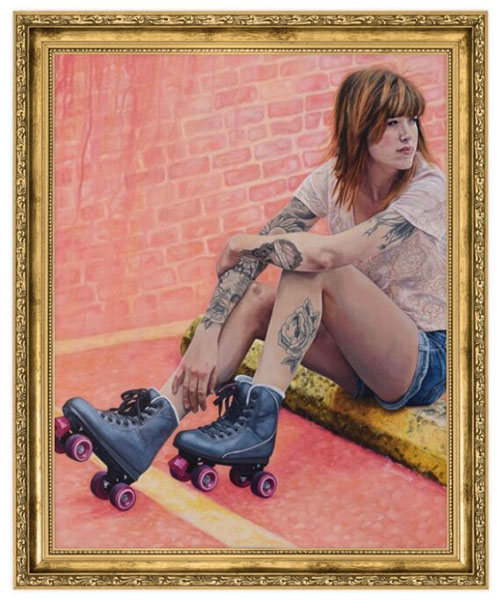

‘Skating But Waiting’

Rachel Linnemeier, BFA’13, spent several years decorating cakes at The Flying Cupcake in Indianapolis. It was “almost like painting with icing,” she says.

Today, she paints with traditional materials, though she still enjoys making birthday cakes for her friends. Linnemeier, who now lives in Tucson, Ariz., mainly creates figurative paintings—artwork clearly derived from real object sources—based on photographs taken by her and her husband.

Since much of her work is self-portraiture, she finds references for poses and attempts to recreate them. Once the photos have been taken, Linnemeier then creates a digital collage to base the final painting on.

“I really like to make sure that I’ve designed the image that I want before I try to translate that photo into a painting,” she explains.

Many of her past paintings have explored the tension between childhood and adulthood. In 2019, she showed two works at the European Museum of Modern Art in Barcelona, Spain, for a “Painting Today, International Women’s Day” exhibition.

“Skating But Waiting” and “A Fine Flutter” featured adults interacting with objects commonly associated with childhood—roller skates and butterfly clips.

“For each artwork, I selected objects reminiscent of childhood and had adults interact with them,” she says. “The golden hair clips and the roller skates may not exclusively be associated with youth but [they] played with the exploration of always being young at heart.”

‘The Pietà’

Aaron Coleman, BFA’09, got his creative start at age 12 when he moved from Maryland to Indiana and was introduced to graffiti.

“Being a part of a group of guys that painted graffiti was my intro to visual culture and art,” he says. “After however many years of that, I decided that I needed to find a different way to make art. I basically didn’t want to go to jail. But I credit graffiti for introducing me to making artwork with my hands.”

Coleman, the Kenneth E. Tyler Chair in Printmaking at IU Indianapolis’ Herron School of Art and Design, now works across media.

“More often than not, I am finding images, or objects, or materials that already exist, that have a problematic history, or a misunderstood history, and I alter those images or those materials to either expose the lie that’s embedded in them or reveal a story that has been hidden,” he explains. “My tendency as an artist is to recontextualize things that already exist.”

Coleman’s 2019 solo show at the Mesa Contemporary Art Museum is a prime example. The collection, titled “True and Livin’” after a Lord Finesse rap song of the same name, included five sculptures and 14 paintings and examines colonialism and its ongoing effects throughout contemporary civilization.

“‘True and Livin’” was a nod to hip-hop and street language but also directly references this idea that these issues that I’m talking about are still very much true and very much alive,” Coleman says.

The paintings in the collection are altered pages from a 1950s coloring book titled Around the Seasons. Over time, the pages changed from white to brownish-yellow, which Coleman says resembles his biracial skin tone. He added black and white acrylic paint to the pages while trying to preserve the line-work of the illustrations.

“Strategically deciding what parts of the image should be black or white, I am able to address stereotypes and notions of racism and bias,” he says.

Coleman also redacted the pages’ text to create “conundrums, poems, and stories of personal or global history and identity.”

He compares the initial application of paint, which is heavily layered, to scars.

“The second application is carded through a laser-cut stencil of the 17th century, colonial crewelwork patterning, or traditional African kente cloth patterning … leading to a high-relief surface that seems to emerge from the scarred surface,” he explains.

Additionally, the sculptures in this body of work point to “a tradition of the exploitation of Black and brown bodies in the industries of labor and entertainment as well as political policy and the criminal justice system.”

In “The Pietà,” Coleman depicts the 36-star American flag that was in use when the 13th Amendment passed. Meanwhile, the Pan-African flag hangs from a golden coat hook in a pose mimicking Christ’s as he lay on the lap of Mary after the crucifixion.

“This sculpture examines the failure of the 13th Amendment as it was followed by Jim Crow as well as the role of the church, for better and worse, during the Reconstruction Era,” he says. “The stripes are formed as red pickets conjuring thoughts of the American Dream, redlining, and protest. The pickets are adorned with bird shit as I wondered what it meant to truly be as free as a bird.”

‘Long Food Line’

For the first 15 years of his career, Francisco Souto, BFA’00, was known for his printmaking. That was until the repetitive, technical printmaking processes led to an arm injury.

“And then I fell in love with drawing,” he says. “After an injury, you have two options. You can cry because you can’t continue the work or you can turn the page.”

Souto started drawing with graphite before colored pencils became his tool of choice. He has developed a hyper-realistic style, to the extent that his drawings are sometimes confused for photographs.

“I use four different [colored pencil] brands from all over the world,” Souto explains. “I work with anywhere from 500 to 700 pencils, because different brands carry different colors and offer different wax and pigment. It’s crazy.”

Souto grew up on a family farm in Mérida, Venezuela—a city in the Andes Mountains. He and his wife moved to the United States decades ago, but his art is still connected to his first home.

“I’ve been living in the States for 27 years,” Souto says. “So, my country is no longer the country that I grew up in. But I got to a point [where I said], ‘Well, now I have a stronger voice. I’m going to make work about my country.’”

Today, many of his artworks are “visual testimonies of the social, economic, and political deterioration that is eroding” Venezuela.

In 2020, Souto showed “Long Food Line,” a striking eight-foot-long drawing created with graphite and acrylic, at the Momentary and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Ark., as part of the “State of the Art 2020” show. It pictures around 100 people standing in line at a supermarket during the economic crisis and food shortages in Venezuela.

“Now, there’s no food, so there are no lines to make,” says Souto of the food crisis during a University of Nebraska, Lincoln interview. “What’s impactful about that piece is there are 100 people patiently waiting in line, but there is only one guard. That power structure was really important for me to replicate.”

The artwork took roughly eight months to complete. When he had the first 50 people drawn, Souto was eager to be done, he says.

“But then I felt like, ‘Well, I can’t leave these people alone. I have to respect they’re here already.’ So, it became kind of a relationship with the drawing,” he says. “And every new individual needs another individual and another individual. That was the energy that pushed me to continue going.”