When Thomas Atkins was 5, he was diagnosed with polio. Doctors said he wouldn’t walk again. But the boy decided otherwise. Sure enough, after three years of wheelchairs, casts, braces, crutches, and rehabilitative therapy, he proved them wrong. The experience taught him that experts were not infallible and that the seemingly undoable was doable.

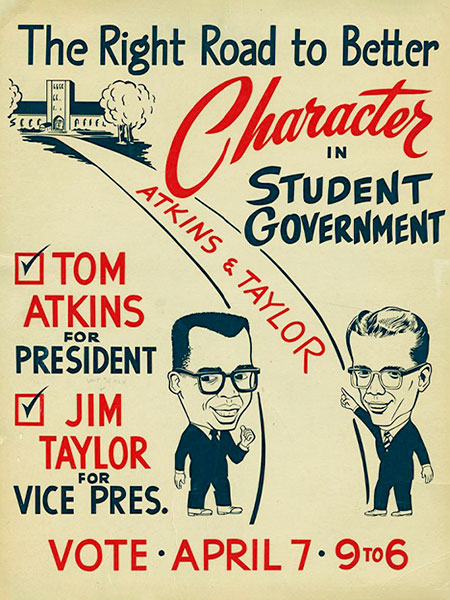

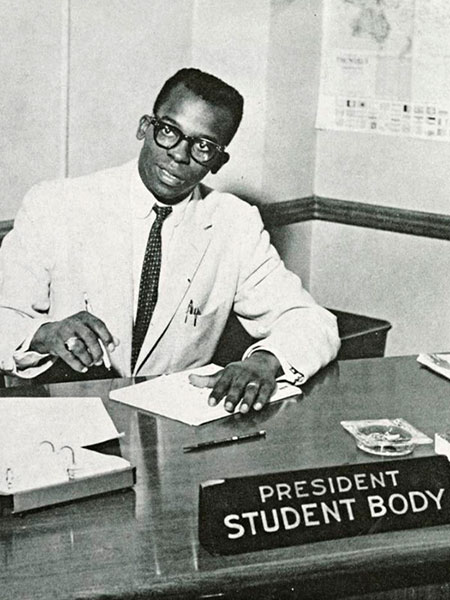

Those lessons served him well at Indiana University. As a scholarship student living in the residence halls in 1960, Atkins, BA’61, bucked the then Greek-dominated student government system and was elected the first Black student body president of a Big Ten university.

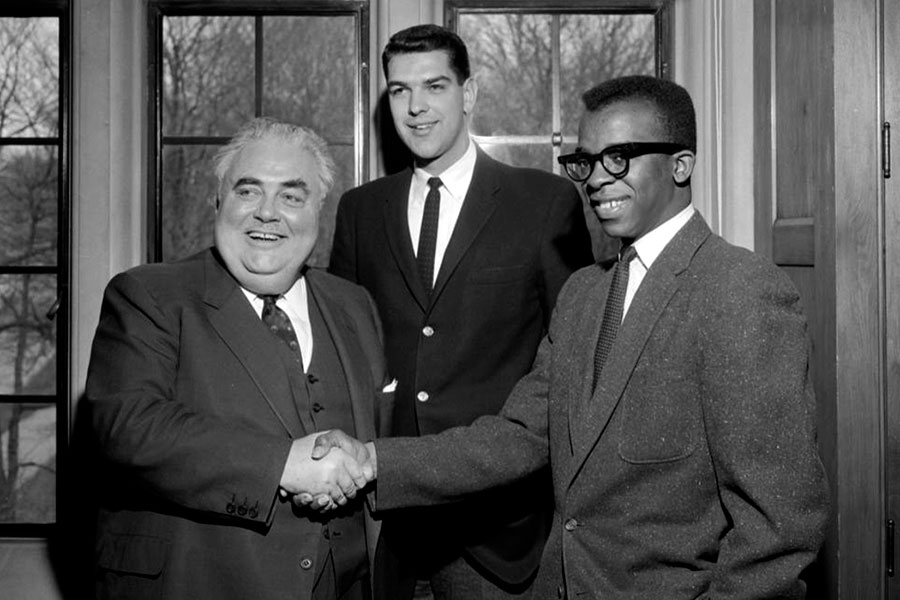

“I remember him very well,” says Herman B Wells, BS’24, MA’27, LLD’62, who was president of IU at the time and a strong defender of civil rights. “He was a very active student and political leader. He inspired confidence.”

Atkins remembers Wells very well, too. “I learned a lot from Herman Wells,” he says. “He was the master of how to do things that you couldn’t do.”

Reinforced and refined by experiences at IU, the lessons Atkins learned as a child stayed with him as he earned a law degree at Harvard University and became a key player in the desegregation of schools and national civil rights causes.

A Thirst for What is Right

Atkins’s sense of fairness and of how the system could be used to achieve it was already evident when he came to IU as a freshman in 1957. Believing students in the dorms lacked influence in campus government, at least partly because they lacked the organization of fraternities and sororities, he set out to increase organization in the residence halls, where he lived.

“I thought it was unfair. I thought it was unreasonable. I thought it was unnecessary, and I set out to change it,” he says. “It wasn’t that the Greeks did too much. It was that everybody else did too little.”

As president of the Men’s Residence Halls Association in his junior year, he was instrumental in combining it with the women’s association. Well-known through those efforts and through having worked in residence hall cafeterias, he beat the Greek candidate for student body president by 45 votes—3,059 to 3,014—that spring.

Shelbyville attorney Steve Moberly, BA’63, LLB’66, worked for Atkins’s election and then became his secretary of campus welfare. He attributes Atkins’s success to his ability to attract crossover Greek votes and to good campaign organization. He describes Atkins as “friendly and outgoing,” a good public speaker who inspired students, white and Black, Greek and non-Greek, and made them believe he was a force for change.

“The civil rights movement was just kind of bubbling beneath the surface,” says Moberly. “He had the rare quality of being able to reach out to white hands and Black hands.”

Moberly says Atkins’s election on an overwhelmingly white campus previously dominated by Greeks was a revolution of sorts.

“His election did break down barriers,” Moberly says. “It was the beginning of the end of student politics organized along housing lines.”

A Vision of Racial Harmony

The youngest of five children and the first in his family to attend college, Atkins says his parents had a lot to do with building his self-confidence. His father, Norse Pierce, and mother, Lillie Mai, left rural Tennessee in hope of better opportunities in the North.

They settled in Elkhart, Ind., where Atkins was born on March 2, 1939. His father had several jobs, including railroad worker and city garbage collector, in addition to being a minister. His mother was a maid for wealthy families.

“My parents, particularly my mother, were insistent that I believe I was as good as anybody else,” he says. “I was told that constantly.”

In 1967, Atkins became the first Black man elected to the Boston City Council and served two-year terms.

David Frick, BA’66, who had been IU Bloomington student body president in 1965–66, met Atkins when both were in law school at Harvard in the fall of 1966. Frick was one of several Harvard law students who campaigned for Atkins when he decided to run for city council.

“He did so against tremendous odds because the minority population in Boston was not substantial,” says Frick, now an attorney in Indianapolis. “At that time, Boston was a very racially divided city.”

In Black neighborhoods, such as Roxbury, which some of the law students had never seen before, they registered voters and asked them to support Atkins.

After getting his law degree, Atkins taught urban politics at Wellesley College and served as secretary of communities and development in the Massachusetts governor’s cabinet. In 1971, he was the first Black man to run for mayor of Boston. He finished fourth, with 12 percent of the vote.

“As young people, we were attracted to people who had a strong vision. He had a strong vision—a vision of racial harmony,” Frick says. “Tom was not angry. He was committed and dedicated to making change happen in a peaceful way.”

Atkins died on June 27, 2008, at the age of 69, after struggling for nearly two decades with Lou Gehrig’s disease.

This article originally appeared in the 1994 March/April issue of the IU Alumni Magazine. It is now part of our Black History Month series, IU’s Black History Makers.