Legendary Loss

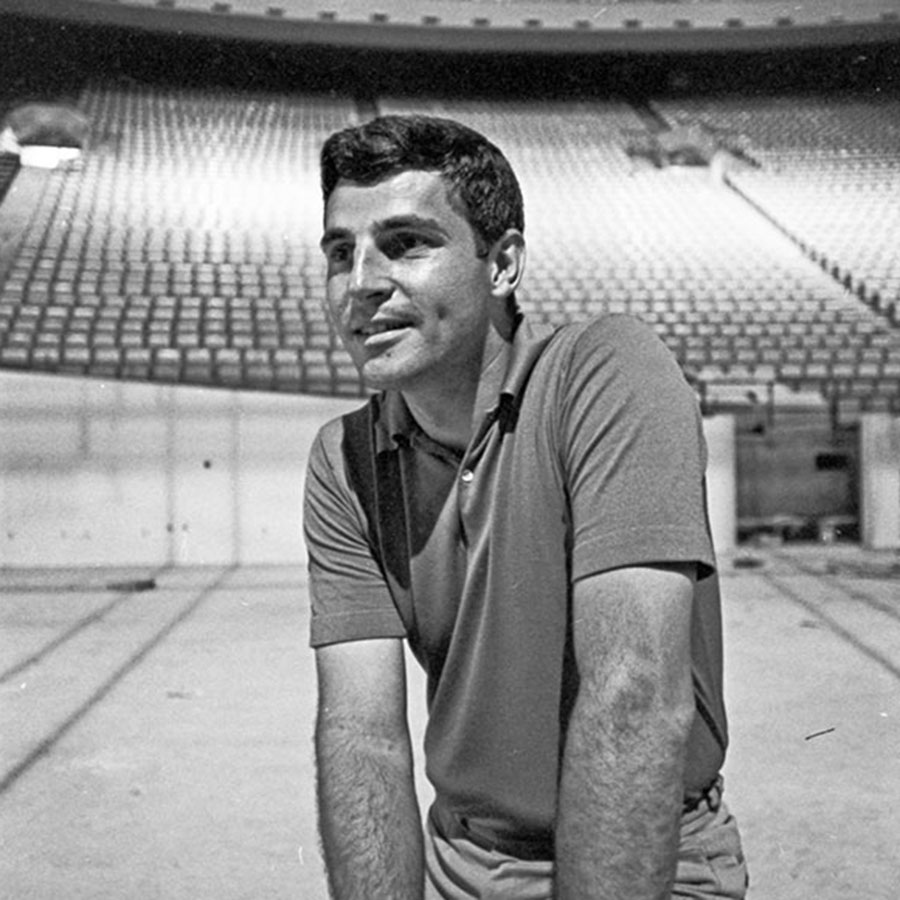

Dec. 1, 1971, was a night of firsts in Bloomington: The first game of the 1971–72 Hoosier men’s basketball season; the first regular-season game played in the newly constructed Assembly Hall; and Hoosier Nation’s first look at its newly hired head coach—a fresh-faced, 31-year-old Bobby Knight.

Knight introduced his intense, defense-driven coaching style to the 14,853 fans in attendance with an 84–77 win over Ball State.

“Defense is the key to winning in any sport, and that’s what I believe in,” Knight had told the Indianapolis Star shortly after his hiring at IU. “Such a change in coaching philosophy at IU will be radical because it was the ‘run-and-shoot’ style that took the Hoosiers to two [previous] championships.”

While unfamiliar to fans, the new approach showed promise—in his inaugural season, the Hoosiers went on to defeat five top-20-ranked teams—but the team fell in the first round of the National Invitation Tournament.

Within a few short years, Knight’s style would prove to be exactly what the program needed to reclaim its spot at the top of the basketball world.

Road to ‘The General’

Born Oct. 25, 1940, in Massillon, Ohio, Knight was raised in nearby Orrville by his father, Carroll, whom everyone called Pat, and mother, Hazel. Knight, who was 6-foot-4 by the time he was a high school senior, was a multi-sport athlete—playing football, basketball, and baseball—and he excelled at all three.

He went on to play basketball at Ohio State under Hall of Fame coach Fred Taylor and was a sophomore on its 1960 NCAA championship team. Knight, a reserve forward, averaged 3.8 points and 2.1 rebounds a game, a stark difference from his high school glory days.

Knight had great respect for Taylor and often sought his counsel. For example—following Knight’s graduation from OSU with degrees in history and government, he took Taylor’s advice and enlisted in the Army in 1963.

“Where there’s a great painting, there’s a great painter. Where there’s a great and unique building, there’s a great architect. Where there’s a great team, there’s a great coach. No team ever won a national championship with a better coach than Fred Taylor,” Knight said of his longtime mentor.

At Army, Knight soon became an assistant coach for the basketball team. In 1965, at 24 years old, he was promoted to head coach—making him the youngest in Division 1 history.

Over six seasons, Knight and his team earned a 102–50 record and made four NIT appearances. One noteworthy player of this era was Mike Krzyzewski, former Duke University head coach and the current most winningest coach in men’s college basketball history, with 1,202 wins.

While at Army, Knight gained a reputation for having an explosive temper, taking a disciplinarian approach, and setting high expectations. He also picked up a nickname: The General.

A New Era in Bloomington

IU took notice of the success and hired Knight in 1971 to succeed Lou Watson as head coach of the Hoosier men’s basketball team. He took what had become a mediocre program and quickly returned it to national prominence.

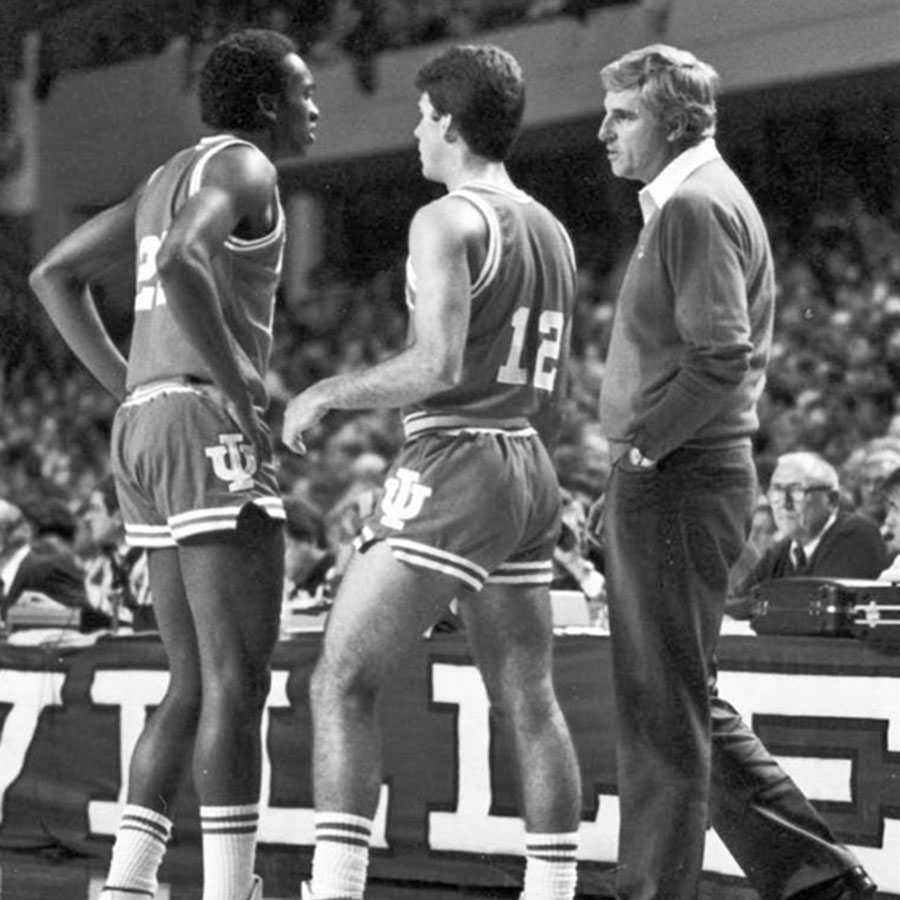

Knight did so by playing the aforementioned man-to-man defense as well as installing an innovative motion offense.

It combined the simple concepts of passing, cutting, and screening with the expectation that players make complex reads and adjustments during play. The approach took time and practice to master.

“It’s not what other people were running back then,” standout Hoosier guard Quinn Buckner, BS’76, told the Associated Press. “[You] had to work as [an opposing] coaching staff on something very different. So as much as it helped us, it challenged other coaches.”

Knight’s offense became trendy, so much so that he published a 29-page book on the subject, Motion Offense, in 1975.

Knight’s high expectations extended beyond the court.

“He influenced my life in ways I could never repay. As he did with all of his players, he always challenged me to get the most out of myself as a player and more importantly, as a person,” recalls current Indiana head coach and former player Mike Woodson, BS’80, who played for Knight from 1976 to 1980.

He emphasized the importance of academics, insisting his players go to class and study. Nearly 80 percent of players under Knight earned their degrees—more than double the national average for D1 schools. At IU during Knight’s tenure, all but four players earned a four-year degree.

Banner Up

Many argue that but for a key injury, Knight’s first championship with IU would have come in 1975: The team made it through the regular season undefeated and spent 11 weeks ranked No. 1.

“My husband called me at work to tell me that the polls had just come out and we were ranked No. 1,” a fan told the now Herald Times. “We couldn’t believe it. In our lifetime we thought only UCLA could be No. 1. Now it was us! In a few days, fans everywhere were wearing buttons saying, ‘Indiana #1.’”

Indiana entered the NCAA tournament with a 29–0 record and an injured Scott May, BS’76, who broke his arm in a one-point victory at Purdue earlier in the season. The Hoosiers reached the Elite Eight round but lost to Kentucky, 92–90.

The Hoosiers came back strong the next season, and their run did not end prematurely—they captured the program’s third NCAA men’s basketball championship in historic fashion.

The 1975–76 season put the Hoosiers in the record books for two unique reasons: The team remains the last men’s D1 team to go undefeated (32–0) for an entire season; and Knight, who was 35 years old, became the fourth youngest coach to be a national collegiate men’s basketball champion. At the time, two of the three coaches who had been younger were his own coach at Ohio State (Fred Taylor, 35 years old in 1960) and IU’s former coach Branch McCracken (31 years old in 1940).

In the final game of the NCAA tournament—in Philadelphia against Michigan—the Hoosiers were down six points at halftime. In the locker room, Knight gave his team a simple challenge.

Scott May recalls Knight’s words: “He said something like, ‘If you want to make history, you’ve got 20 minutes. There [are] no adjustments we need to make. It’s just whether you want to go undefeated or get beat by Michigan.’ I think we played our finest half of basketball.”

The Hoosiers ran away from the Wolverines, winning 86–68. Under Knight’s leadership, IU was again a basketball powerhouse and would remain a top contender for the following two and a half decades.

IU’s next banner came in 1981 when the Hoosiers defeated the North Carolina Tar Heels in the NCAA championship game, also in Philadelphia. At the time, this championship run—led by guard Isiah Thomas, BA’87—was considered by some to be Knight’s greatest achievement, because of the season’s rocky start. In fact, the 1980–81 team—with a record of 26–9—became the “losingest” team to win the NCAA tournament.

Sportswriter and longtime friend Bob Hammel, ’57, told the Indianapolis Star: “By the time they were cutting down the nets in Philadelphia, I think they could’ve played that ’76 [Hoosiers] team better than anybody I can recall.”

Six years later, in 1987, Knight brought home another national championship, and it came in dramatic fashion. In the championship game—in New Orleans against Syracuse—the Orange were up a point with less than 30 seconds remaining.

Junior guard Keith Smart, BGS’95, takes it from there: “When it got to 10 seconds and Steve [Alford, BS’87] was covered, I had to penetrate and try to get the ball to Daryl [Thomas, ’87]. When he was covered, he kicked it back to me. I never looked at the clock. I just shot.”

The 18-footer was good, and the Hoosiers were champions again.

“This was a team that three seasons ago could not hold a lead and was always vulnerable,” Knight said after the championship game. “These kids have come a long way to get here. I’m really not sure yet if we’re that good a team. But I could not be happier for them.”

Honors with a Shadow of Controversy

At Assembly Hall, across the court from the treasured national championship banners, are other banners, which provide evidence of Knight’s long-term, consistent success at IU: one NIT championship (1979); five Final Four appearances (1973, 1976, 1981, 1987, and 1992); and 11 Big Ten regular season championships (1973, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1980, 1981, 1983, 1987, 1989, 1991, and 1993).

His individual accolades are also plentiful: four-time National Coach of the Year, five-time Big Ten Coach of the Year, and an inductee into the IU Athletics Hall of Fame, the College Basketball Hall of Fame, and the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

Knight’s preference, however, was to keep the focus on the team and his players: “I’ve never felt comfortable with the award ‘Coach of the Year’ or coach of anything,” he once said of his honors. “I think there’s a much more appropriate nomenclature that could be used, and that would be ‘Team of the Year.’”

In addition to collegiate basketball, Knight’s coaching excelled on the global stage. His team won gold at the 1979 Pan American Games in Puerto Rico with several Hoosiers on the roster: Isiah Thomas; Ray Tolbert, BS’81; and Mike Woodson. In 1984, Knight coached Team USA to gold at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles with leading scorer Michael Jordan and sharp-shooting Hoosier guard Steve Alford.

Knight’s gold in Puerto Rico, however, was marred by outbursts: Knight was ejected from the first game for arguing with the referees. Then, at a practice, he was arrested for assaulting a police officer during a dispute over the team’s early access to the court.

Other incidents included throwing a chair across the court after receiving a technical foul during a home game against Purdue in 1985; inappropriate comments during an interview on NBC with Connie Chung in 1988; and numerous accounts of directing fury toward players, referees, and members of the media.

“When he was good, there was no one better than Bob Knight. He was generous. He cared about his players. He was the best,” said sportswriter John Feinstein, who profiled Knight and the Hoosiers in his book A Season on the Brink, during an NPR interview.“When he was bad, there were few worse.”

Inside the Hall

In 1985, Feinstein—a basketball writer for The Washington Post at the time—was at work on A Season on the Brink and was given unprecedented access to Hoosier basketball. He was permitted to observe the team’s historically closed practices, attend strategy meetings, listen to Knight’s private conversations with players, and even be part of game huddles.

The book came at a pivotal point of Knight’s IU career. After coaching the U.S. team to Olympic gold in 1984, Knight was seemingly at the pinnacle of his profession; however, in a matter of months, he was coaching a struggling Hoosier team, causing some to ask if his legendary career was in decline.

Knight allowed Feinstein to document it all. And he did—the first chapter gives the reader a courtside view of what many would call abuse: Knight verbally berating players at an early-season practice, storming out of the locker room, returning to yell more, and storming out again.

Direct quotes include plenty of profanity (even after some heavy editing by Feinstein) and descriptions of Knight’s voice going hoarse from yelling.

While Knight’s explosive temper was no secret, the book showed another, often overlooked side: Knight’s total dedication to his players, his extreme value of education, and his acts of compassion and generosity toward players and fans. It also showcased Knight’s popularity throughout the state of Indiana.

The book was a huge success, quickly becoming a New York Times bestseller. Knight, who, according to Feinstein, never complained or tried to back out of the project, publicly expressed his disdain for the book and its author.

Feinstein ends the acknowledgments of his book with this: “I did not discover or write about a saint, but about a driven and brilliant coach; a flawed man, but a good man. I felt that way about him when I started the project. I felt that way about him with I finished it.”

The Era Ends

Following the struggles of the 1985–86 season, the program bounced back with its 1987 championship. Subsequent seasons brought great success, but controversy around Knight’s behavior continued and eventually came to a head.

After years of inappropriate conduct and allegations—both on and off the court—IU could no longer ignore Knight’s behavior. In 1999, following the release of a video from a 1997 practice that showed Knight grabbing player Neil Reed, ’97, by the throat and appearing to choke him, the university instituted a “zero-tolerance” policy for the coach.

The guidelines prohibited inappropriate physical contact and required proper behavior in public when representing IU. Ultimately, in the fall of 2000, an interaction with a student at Assembly Hall triggered a policy violation. Knight was offered the opportunity to resign but declined. He was fired Sept. 10.

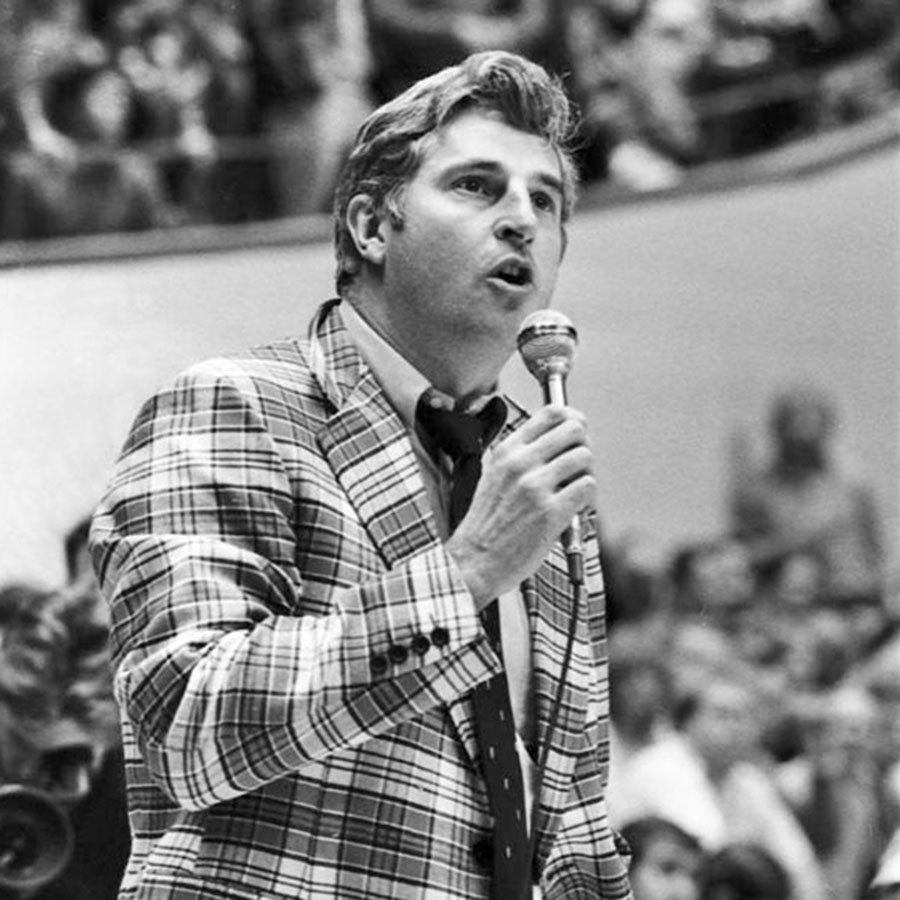

As news spread, chaos erupted on campus and the media descended on Bloomington. The next day, Knight addressed a crowd of close to 10,000 people—bashing university officials and calling for support of the team.

“The same support that our teams have had for 29 years is the same support these kids playing on this team this year should get from you,” Knight told the crowd.

He went on to coach at Texas Tech University for seven seasons before retiring mid-season in 2008 and passing the team to his son, Pat Knight, BS’95. He finished his coaching career as the winningest coach in college basketball with 902 wins. He now ranks sixth.

After his retirement from coaching, Knight was a commentator and analyst for ESPN until 2015.

Overdue Homecoming

Fast forward almost 50 years from that first game in 1971—past the record-breaking wins and devastating losses; the championship banners and numerous controversies; a zero-tolerance firing and 20 years of bad blood. During halftime of a Purdue game on Feb. 8, 2020, Knight made his return to Assembly Hall.

Flanked by generations of former players, including Pat Knight; Quinn Buckner; Steve Green, BA’78, DDS’84; and Scott May; Knight made his way to half court and led a packed arena of enthusiastic fans in a chant of “defense, defense”—a not-so-gentle reminder of his coaching philosophy.

“I don’t think anything meant more to Coach Knight than the relationships he developed with his players,” said Fred Glass, BA’81, JD’84, IU vice president and director of athletics at the time, following Knight’s return. “It’s great that he is able to enjoy this moment with so many of them, and we are very pleased to welcome him back.”

Many, seemingly himself included, had thought Knight would never return to Assembly Hall.

“We had a historic day,” said Buckner, an anchor on Knight’s undefeated 1975–76 team. “The only thing that matters is that Coach came back to Bloomington, and he came back to IU. What was here before is gone.”

Written By

Lacy Nowling Whitaker

Lacy, a Bloomington native, earned two degrees from IU Bloomington (BA’08, MA’14) and is the Director of Content with the IU Alumni Association.