This story was originally published in the Feb. 28, 2013, issue of the Indiana Daily Student, and won first place in the Hearst Journalism writing competition for personality profile.

Note: This article contains a racist slur.

The forgotten queen steps onto the empty stage.

She looks out across the cavernous hall of the IU Auditorium. It’s bigger than she remembered. She sees the rows of seats where her friends cheered for her. She feels the crown tilting on her head, hears the flashbulbs popping in her face, catching her surprise as she made history. She never expected to win.

The stage is so quiet now. She thinks back to the Ebony fashion tour that followed her coronation, the dinner with Dr. King. She thinks about the slurs people hurled at her, writing letters, calling her at the dorm. The way her own yearbook ignored her reign. The man pointing the gun.

So much pride and so much hate, all beginning under these lights.

Nancy Streets-Lyons, BA’62, was the first and last Black Miss IU, decades before a Black woman would be named Miss America.

She is 73 now. Her eyebrows are thinner than they were in the old photos—her hair has turned gray. When she descends a staircase, she takes each step carefully. But there’s still a bob in her walk, and when she smiles, her cheeks break into the same dimples that charmed the pageant judges. She’s not afraid to speak her mind. She’s funny. She’s warm. Whenever she meets someone new, she offers a big hug.

“Oh, please,” she says. “Call me Nancy.”

She grew up in South Bend, Ind., where she attended the old Central High School. Her family had traces of not just African American blood, but Cherokee, Irish, and Scottish. Her great-great-great-grandmother was Jewish.

One of four children, Nancy was raised in a home that embraced diversity. Her parents were involved with the local NAACP. Her mother was an advocate for the rights of migrant workers and often invited them to join the family at dinner. Her father had gone to IU to be a dentist. Her brothers and cousins studied here, too. When it was time for her to go to college, heading south to Bloomington was an easy decision.

If she had the choice again, she wouldn’t pick IU. After everything she went through, she says, she wouldn’t attend such a large university. Five decades have come and gone since she left this place.

Civil rights legislation was passed and segregation became just a bad memory for generations.

Photographs and history books are all that remain of the Little Rock Nine, the Selma and Montgomery marches, Rosa Parks, and Malcolm X.

A Black man was named president of IU. Another was elected president of the United States.

Nancy was married, had three children, and divorced. She worked as a sales representative and for a few years as an English and arithmetic teacher. She fought a rare type of throat cancer. Today she lives in Indianapolis, where she works as an in-home caregiver with Senior Home Companions of Indiana. She fixes meals for and watches over two elderly clients part-time, five days a week.

For years, she didn’t think about the institution that had lifted her up and then knocked her down. Then, last fall, the phone rang. IU wanted its queen to come home.

When Nancy arrived as a freshman in 1957, Bloomington was a community in transition. Because of the liberal leanings of IU and the integration policies of Herman B Wells, BS’24, MA’27, LLD’62, the city was more progressive than much of the state. But IU and Bloomington were by no means immune to racism.

Only 30 years before, the Ku Klux Klan had dominated state politics and still had a presence in southern Indiana. Many businesses and restaurants were still operating under the policy of “separate but equal.” Nick’s English Hut only started openly serving Black customers the year Nancy started classes.

“Bloomington was not a very nice place to be for Black people. How it was that young people went there, they had extreme stamina and patience,” Nancy says today. “You really had to pay attention to what you were doing.”

If you were Black, you didn’t go to the east side of the square downtown, she says.

Black students sometimes had to travel in groups as a precautionary measure.

The residence halls had been integrated for 10 years, but white students were assigned white roommates, Black students were assigned Black roommates. When Nancy applied for admission, she sent in a card with her photo and basic information for housing assignments. She had checked the box for “negro,” but someone at IU had just looked at her photo and thought she was white. They assigned her a room with a white girl in the women’s quad, now Goodbody, Morrison, Sycamore, and Memorial halls.

Her roommate didn’t care, but Nancy felt uncomfortable. She moved in with her cousin in Smithwood Hall, now Read Center, to “keep the peace.”

While living in Smithwood, she pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha, a historically Black sorority. In the spring of her sophomore year, the members of AKA selected Nancy to be their representative in the Miss IU pageant.

“We’re going to enter you because your major is speech and theater,” she remembers them telling her. “Don’t worry about it—we know you won’t win, but we want to be represented.”

The Miss IU pageant was one of a plethora of contests that gave titles to co-eds. There was the Queen of Indiana University, the Sweater Queen, Miss Overseas, the Homecoming Queen, the Wellhouse Queen, and the Waltz Queen.

But Miss IU would go on to vie for the Miss Indiana title and, possibly, Miss America.

Nancy had never competed in a beauty pageant before. She borrowed the one-piece bathing suit and white gown she wore from a fellow AKA pledge. The AKAs kept her up all night, helping her prepare and showing her how to walk.

Before she took the stage at the IU Auditorium, she prayed to be peaceful, to be calm, to be serene.

“I took my prayer book with me to the contest, but I didn’t think I’d win it,” Nancy said to an AP reporter after the pageant. “I’ve been prayerful all week, and my boyfriend and sorority sisters had been praying with me.”

The contestants were judged in five categories. The swimsuit and evening gown competitions, a talent competition, a general interview, and “on- and off-stage poise and charm.”

Nancy performed a modern dance in a red leotard to “Harlem Nocturne,” a haunting jazz standard.

At the end of the night, Nancy was selected as one of three finalists. She was so sure she wouldn’t win, she started to move offstage before realizing the judges had picked her.

“We were waiting for you to make one mistake, and you didn’t,” Nancy recalls one of them saying. “So, we had to honor that.”

The AKAs in the audience started cheering and rushed to the stage. Someone put a sash over Nancy’s shoulders and handed her a huge bouquet. She kneeled down so that Anita Hursh, the 1958 Miss Indiana, could place the crown on her head. Hursh couldn’t get it on straight, so the crown sat tilted on Nancy’s head, slightly off-center.

A flashbulb popped. That image would end up in LIFE magazine, right next to an image of President Dwight Eisenhower and just above some of the first images of the Earth from space.

Fifty-four years later, on a cold Sunday evening in February, Nancy sits in the dark Willkie Auditorium, watching nine contestants competing for Miss IU 2013.

The pageant’s executive director has invited her back to Bloomington to be honored in this year’s ceremony. Nancy’s story is an important chapter in the contest’s history, and that history is hard to come by.

In the mid-1960s, the pageant was moved off-campus due to lack of sponsorship. Miss IU did not come back in its current incarnation until 2006. Today, the pageant is a student-run scholarship organization that operates year-round in charitable and civic activities.

Nancy and her daughter, Shannon Houston, sit in the front row. Of the nine contestants, there is one Black student, Arika Casey. She’s tall, with long, curly hair. Just like Nancy did, she performs a contemporary dance. Nancy leans forward and applauds with her hands held high.

Later, the women walk across the stage in high heels and tiny bikinis that leave little to the imagination. Shannon turns to her mother. Did they have a swimsuit competition when you were here?

“Yeah,” Nancy says. “But not like this.”

Nancy’s crowning made the front page of the Indiana Daily Student and the Bloomington Herald-Telephone. One headline read, “Negro Coed Wins ‘Miss IU’ Title.” She flew to New York to be on national television and to Hollywood for a screen test with Columbia Pictures. She remembers them telling her she’d be the new Lena Horne, the new Dorothy Dandridge.

“There’s no way you could replace icons like that,” she says. “I think they just wanted a light-skinned Black person. They wanted to strike while the iron was hot. I knew I didn’t have the maturity at the time.”

Meanwhile, IU President Herman B Wells was inundated with hate mail.

“For the first time since I left the university, I have been ashamed to say I received my education there,” wrote [one alumna]. “I cannot understand how you and your faculty could allow a colored girl to be chosen as queen.”

Nancy’s parents took her to the Miss Indiana contest in Michigan City, Ind. Before the pageant, the contestants were originally slated to ride together in a parade. But Nancy was assigned to a segregated float, away from the white contestants.

Nancy’s mother started to protest. Her daughter was here to represent all of IU, not just the Black community. Why was she being shoved aside? But Nancy didn’t want to cause a fuss. She told her mother she’d be fine on the separate float.

She lost the Miss Indiana pageant to a white girl from Chicago, 1959’s Miss Valparaiso University.

“The Miss Indiana contest in Michigan City—that was a joke,” she says. “I don’t want to say anything else.”

When she returned to IU, she was excited to get her copy of the Arbutus yearbook. The Arbutus traditionally devoted a section to the university’s many pageant winners.

Nancy flipped through the pages, looking for her face. But there was no mention of Nancy or the Miss IU pageant. Instead, on pages 72 through 79, there were full-page portraits and interviews with “the Queen of Indiana University,” a white woman and her court.

Nancy wasn’t in the following year’s book, either. It took until 1988 for the Arbutus to recognize her title.

“It was like they were saying I was less than a human being. They’d given me this title and this crown, and then they wanted to sweep it under the rug and forget it ever happened,” Nancy told the Arbutus in an interview that year. “I was a ghost.”

By then, she had long since put away every reminder of the pageant. Her crown, her sash, her gown from Miss Indiana, all the newspaper clippings and letters of congratulation and of hate from as far away as Africa and Europe—all of it she hauled to the attic.

On the day after the 2013 pageant, a group of graying alumni sits in the Tudor Room of the Indiana Memorial Union, waiting for Nancy. She’s being honored at a luncheon for Black alumni.

George Taliaferro, BS’51—the first Black man to be drafted into the NFL—remembers not being allowed in the Tudor Room while he was a student. Two years before Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, Taliaferro was the star tailback for the Hoosiers and led the team to their only undefeated Big Ten championship to date.

“And I still couldn’t sit in this room when I was here,” he says.

As he and the other Black alumni wait for Nancy, they think back to other memories from their college years. Remember going out to The Hole on the weekend for dancing, drinks, and soul food? Remember when the Black Market, a hair salon and music store, was firebombed?

When Nancy arrives with Shannon, the group moves into the Coronation Room, surrounded by portraits of 19th-century white men. Nancy greets Taliaferro with one of her signature hugs, even though they’ve never met.

“Did you know Fitzhugh Lyons?” Nancy asks him.

Lyons was Nancy’s father-in-law and was one of the first football players for IU in the early 1930s. From the sidelines, fans called him “nigger.” He wasn’t allowed to eat with his fellow students, couldn’t stay with them, couldn’t join them at the movies.

“Remember,” Nancy says. “Fitzhugh was better at basketball, but …”

Taliaferro and Shannon finish the sentence with her. “… they weren’t going to let him play.”

As they eat, Nancy smiles, listens to the other’s stories, and tells about the pageant. She talks about how there are still undercurrents of racism everywhere. The fight for equality doesn’t end at skin color, either, Nancy says. She finds the struggle for GLBT and women’s rights is reminiscent of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

She shares one of her favorite quotes, something from Maya Angelou:

“When you know better, you do better.”

After the 1959 pageant, Nancy was invited to participate in Ebony magazine’s Fashion Fair. At 19 years old, her mother said she was too young, but the next year, in the fall of 1960, she boarded a bus with other young Black women and toured the country, going deep into the South.

They went to Houston and Little Rock, Ark.; Chattanooga, Tenn.; and Jackson, Miss. They were in North Carolina only eight months after the Greensboro, N.C., sit-ins. They were in Atlanta, where Nancy had dinner with Martin Luther King Jr.

It was three years before King stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to tell America of his audacious dream.

The march from Selma to Montgomery was still three years away. Jim Crow was alive and well in the places Nancy stopped, like Dallas and Mississippi, but Nancy didn’t have to go far from home to experience the worst of segregation.

On April 13, 1962, three years after she was named Miss IU, Nancy and several of her friends heard that a Bloomington roller skating rink had turned someone away due to the color of their skin.

“So we got some people together,” Nancy says, “and we went there to integrate it.”

When Nancy arrived with two Black friends and three white friends, owner Robert Jones told them it was a members-only club. He went to his office and came out with a handgun.

At the sight of the gun, the group decided to leave peacefully. A mob of white patrons followed them.

“We were very lucky we didn’t get shot,” Nancy says.

In the days and weeks after the incident, Nancy and her friends lodged a complaint with the newly formed Indiana Civil Rights Commission. The case was heard in May 1962 in the Monroe County Courthouse to determine whether Jones’s rink was a private club and if not, had he denied access based on race. It was the first hearing of the ICRC, the first time the commission’s power to call a hearing was tested in practice.

Nancy and her co-defendants testified to the events of the night at the Roll-O-Rama.

IU Dean of Students Robert Shaffer served as a character witness and testified that the students were “good citizens.” Other white students testified that the rink had never asked for a membership card before. Jones didn’t even show up.

The ICRC ruled that Jones was in violation of the state’s Public Accommodations Law, but the young commission had no power to charge him with a crime.

Nancy felt they never stood a chance of getting any real justice. It was just one more slap in the face to the Black community at IU.

After the lunch at the Tudor Room, Clarence Boone, BA’53, MD’56, director of diversity programs for the IU Alumni Association, takes Nancy to the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center. As the car drives down Seventh Street toward Showalter Fountain, they pass students walking to and from class.

“This is a beautiful campus,” Nancy says, looking out the window.

“There’s a lot of memories, good and bad,” Boone says, “but we’re doing our best.”

“That’s the most important,” Nancy says.

Inside the Black culture center, a large display remembers Black leaders from IU’s history. A panel labeled “Change Agents” shows photos of Herman B Wells, Marian Anderson, and Bill Garrett, BS’51. Anderson was the first Black woman to perform at the White House. Garrett was the first Black basketball player at IU and in the Big Ten.

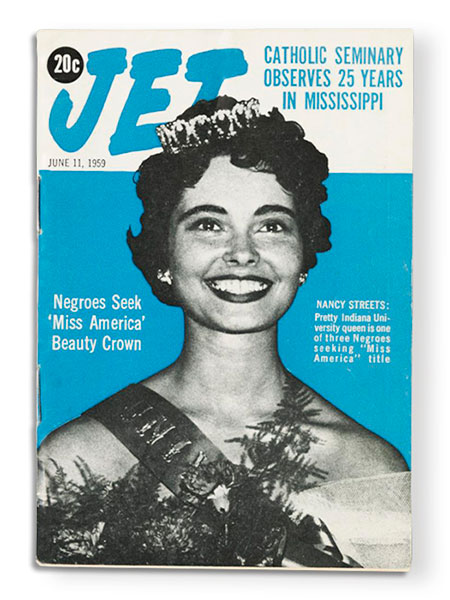

Below these icons, Nancy’s face smiles from the cover of Jet, showing her on the night of the pageant.

“There you are,” Shannon says, pointing.

There she is, beaming under the lights. There are her roses, her sash, the off-center crown.

“I was all of 19 years old,” she says, putting on her glasses. “Lord have mercy.”

Nancy and her daughter sit in the Village Deli on Tuesday morning to have breakfast before going back home to Indianapolis. Teresa White, BS’85, MS’93, executive director of the Miss IU pageant, joins them.

Chuck Berry songs and jazz standards play over the loudspeakers as they eat Californian scrambles and extra-large buttermilk pancakes.

Nancy says she’s impressed by how much freedom students enjoy today. They don’t need to check a box that says “negro” to decide their roommate. They can live with whomever they please, man or woman, white or Black.

Five decades ago, all that would have been impossible.

“We had a great day yesterday,” Nancy says. “What you have on this campus in this day and age is just phenomenal.”

“It’s your campus too,” White says, her hand on Nancy’s shoulder. “You’re part of this too.”

The conversation turns to the ugly letters Herman B Wells received after the pageant. White has read them. Nancy is intrigued. She wonders what the letters said.

“How vulgar were they?” she asks intently. “Tell me what they said.”

The letters are in the IU Archives. The worst was a five-page rant by a man from Raleigh, N.C., who called Nancy “a thick-lipped, flat-nosed … negress.” Others called her title an “abomination,” that it was evidence of a “communist infestation” on campus.

Later, when she hears these things, Nancy laughs.

“I may be 73 years old,” she says. “But I’m pretty thick-skinned.”

She wants the IU Archives to scan the letters and make them available on its website. It’s like her Maya Angelou quote. People today need to know how awful that time of IU’s history truly was. Otherwise, how can we learn to be better?

“Put it all online,” she says.

Before they invited her back, Nancy didn’t intend on returning to IU. Everything that had happened to her, the slights and insults—she had pushed it aside and moved on. She was surprised they even called.

“It’s bad to harbor bad feelings,” she says. “I felt like that for a long time.”

But as soon as she was back in Bloomington, everyone made it clear she had not been forgotten. Every place she went on campus, people knew who she was and were excited to meet her. They invited her to breakfasts and dinners. They asked her to speak on the radio. A curator at the archives asked her to come back again so they could tape-record her history and place it in the archives. The Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center invited her to return in April as a guest of honor at a reunion celebration.

At the pageant, when Nancy and Shannon were watching the young contestants, the emcees invited her up to the microphone to share memories of her own crowning.

Then she turned to move offstage.

“Wait, Nancy,” said the emcees as the 2012 Miss IU walked onto the stage with a large bouquet of roses. “Come back.”

Just like when she was 19, she was surprised to be called back under the lights. She received the bouquet and tried to walk away again. But they wouldn’t let her.

“Oh, Nancy, come back,” they said. “I think they want to get a photo.”

She turned around, still smiling, the bouquet cradled in her arms, as camera flashes and applause filled the air.

“Do I deserve all of this?” she asked herself. The pain had faded away. Instead, she felt blessed. “Humility. Just humility.”

This story is part of our Black History Month series, IU’s Black History Makers.